Matlock Cable Tramway

History

Matlock's 3ft 6ins-gauge cable tramway, which opened on the 28th March 1893, was owned and operated by the Matlock Cable Tramway Company Limited, itself formed in late 1890.

The idea for the tramway came from a local man — Job Smith — who had seen San Francisco's cable trams first hand in the early 1860s, and who realised that this form of traction would be ideal for visitors to Matlock's hydrotherapy establishments, which were all situated on Matlock Bank, some 300ft above the valley floor. Smith had once worked for John Smedley, one of the town's hydrotherapy entrepreneurs, and on his return to the town, sought, unsuccessfully, to persuade Smedley to finance a cable tramway. There matters lay until the mid-1880s, when the reins were taken up once again, and though more progress was made this time around, the initiative eventually stalled due to a lack of finance. In 1890 however, almost 30 years after Smith's visit to the USA, and by which time he was a member of Matlock Local Board, a sequence of serendipitous events led to an offer by Matlock-born George Newnes (later Sir George Newnes) to finance the tramway. Newnes was a well-known publisher and philanthropist, who seems to have had something of a penchant for steep railways/tramways, eventually being involved in three funiculars, in addition to the cable tramway at Matlock.

The Matlock Cable Tramway was exactly half-a-mile long, running from Crown Square in Matlock Bridge, approximately 200 yards from the Midland Railway station, up Bank Rd and Rutland St to Wellington St, where the car shed-cum-winding house was located. The roads up which the tramway ran were very steep — 1 in 6.5 on the severest section, though this has often been mis-reported as 1 in 5.5 — which made the line the steepest street tramway in the world. Although short, the line was unfortunately far from straight, which was to have serious consequences for cable longevity throughout the undertaking's life.

The tramway was an immediate success, carrying a staggering quarter of a million passengers during its first season, and paying its one and only dividend, before the perennial — or to be more precise, initially biennial and later annual — problem of cable replacement reared its ugly head. Like many tramways primarily serving tourists and visitors, Matlock's income depended heavily on a good summer season, during which intense operation was often necessary (with the higher costs of an extra car and crew), whilst winter operation ran at a loss, a situation which was never fully addressed.

The next notable event in the history of the tramway saw Newnes buy out his fellow shareholders and then gift the tramway to Matlock Urban District Council. It is unclear why he did this, though it was almost certainly a combination of his philanthropy, coupled with a need to concentrate on his other ventures. The council took possession on the 24th June 1898 and soon made plans to extend the line, even obtaining a parliamentary order, though when the financial reality of operating the tramway began to make itself felt, plans for expansion were quickly dropped.

During the first 10 years or so of council ownership, the tramway usually made a small profit, interspersed with the odd loss, but the next ten, from 1911 onwards, were to be marked by continual, though not substantial losses. During this period, the council effectively treated the tramway as a subsidised public amenity, providing an important service to both locals and visitors. The Great War was however to bring much more severe challenges, with railway excursion traffic — a vital source of passengers — all but stopping, whilst difficulties obtaining spares, particularly new cables, actually caused the tramway to close for several weeks in 1917.

The optimism of 1919 soon gave way to constant struggle, post-war inflation pushing costs up significantly, made worse by issues with the quality of key components (cable grippers) and the need to replace worn-out equipment, particularly the steam generation equipment. Whilst obviously concerned about the mounting losses and debt, the council was still committed to the tramway, borrowing money to replace the condemned boiler with a much more efficient gas power plant (in early 1921). Although this move helped with fuel costs, other costs had risen to the point where the council's outlay could not possibly be recouped through fares, a situation not helped by the tramway continuing to run at times (e.g., winter) when it was poorly patronised. As a result, costs and losses in the 1920s rose to what were unsustainable levels for a small council, with motorbus competition now adding to the tramway's woes.

The members of the council and of the Tramways Committee argued endlessly amongst themselves about the future of the tramway, but took little in the way of concrete action, finally leaving that to its enlarged successor — the 'Matlocks UDC’ — which was formed on 1st April 1924. The new council fared little better, arguing at length (and vociferously) over the tramway and various schemes for its replacement, the end result being that the undertaking was allowed to limp on, changes to services having some impact on the losses, but not nearly enough to save it.

After innumerable debates and disagreements, many of them taking place in the local press, the Tramways Committee voted to abandon the tramway on the 8th July 1927. This was however not the end of the fight, a public campaign subsequently forcing the council to call a meeting to explain their decision, which took place on the 12th August 1927. After yet more heated discussion, the decision to close the tramway was put to a show of hands in the meeting, which supported it by a substantial majority, though there were accusations that the vote had only taken place after a significant number of people had already left the meeting.

Although the council decided to close the tramway on the 30th September 1927, the ever-troublesome cable was to have the last say, breaking (or rather fraying) on the 23rd September, services finishing for good one week earlier than planned.

The trams were replaced by motorbuses (run by private companies), though they reached the top by a much more circuitous route, the direct hill proving to be beyond the capabilities of the replacement technology.

Uniforms

The history of Matlock's tramway falls into two distinct periods, from the opening in March 1893 through to June 1898 (under the auspices of the Matlock Tramway Company Ltd), and thereafter until its closure in September 1927 as a municipal concern (initially under the auspices of 'Matlock UDC' and latterly the 'Matlocks UDC'). The MTCoLtd certainly issued its staff with uniforms, though close-up photos only reveal sufficient detail to confirm that long-sleeved waistcoats were worn, along with kepi-style caps; the latter appear not to have carried a cap badge, though this cannot be stated with certainty. The waistcoats bore metallic buttons and had sleeves of a lighter-coloured material than the main body, a style that remained in favour in the subsequent municipal era.

New uniforms were issued in November 1898 following the gift of the system to Matlock UDC in the summer of that year; these comprised blue jackets with red piping, brown cord trousers and long-sleeved waistcoats, along with a kepi-style cap. Photographs suggest that the sleeves of the waistcoats were a different material than the main body, possibly the same cord used for the trousers; the jackets had four metal buttons and the waistcoats five. Given that the council is known to have used local suppliers for the uniforms throughout the municipal era, the buttons were more than likely plain, i.e., unmarked; it is of course possible that the council had their own municipal buttons manufactured and provided to local tailors, though there is absolutely no evidence to support this.

Unusually for a tramway system, the kepi-style caps did not carry a cap badge. A simple number badge was however introduced in late 1899, ostensibly so that the public could identify individuals they wanted to complain about, but these appear to have quickly fallen out of use. The kepi caps were replaced — in the late Edwardian era — by more modern looking military-style caps with tensioned crowns (tops); they continued to be devoid of badges right through to the closure of the system in 1927. Given that the council used various suppliers over the course of the tramway's lifetime, the cut of the jackets inevitably changed subtly down the years, as fashions altered and the council's purse-strings tightened, though the one constant appears to have been the complete lack of badges. Photographs suggest that in later years, tramcar staff sometimes turned out in completely informal attire, including flat caps.

The MTCoLtd and Matlock UDC also provided drivers and conductors with topcoats/greatcoats, though precisely what form these took is currently unclear. The council apparently ceased this practice during the Great War, and tramcar crews were thereafter expected to supply their own winter clothing.

The tramway did not employ inspectors, and unlike the vast majority of UK tramway systems, it did not employ the services of women during the Great War.

Further reading

For a history of the tramway, see: 'The Matlock Cable Tramway' by Glynn Waite; Pynot Publishing (2012). I am indebted to Glynn for all the photos below, as well as the background information above and the captions below.

Images

Cable tram drivers and conductors

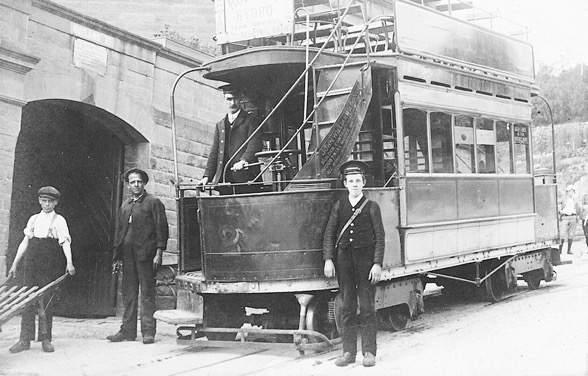

Tramcar No 1 stands at the bottom of Bank Rd — photo undated, but probably taken in the mid-1890s. The youthful-looking conductor (on the steps) is wearing a long-sleeved waistcoat and a kepi-style cap, seemingly without a cap badge. Photo courtesy of the Glynn Waite Collection.

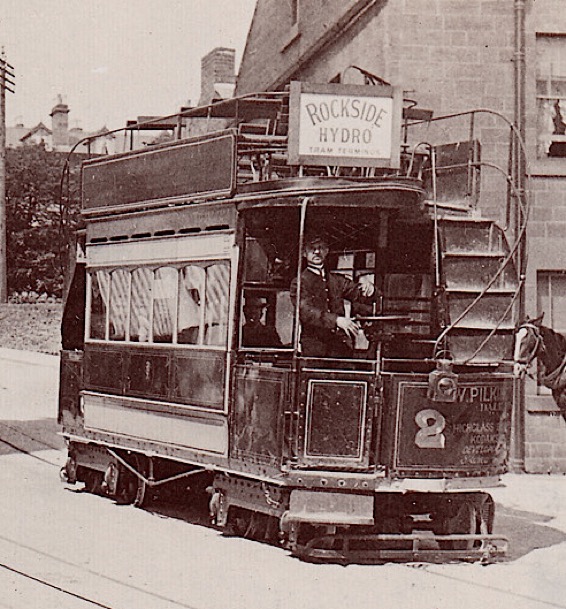

The crew of a fairly pristine-looking Tramcar No 2, devoid of adverts, stare intently at the cameraman, who has captured the scene at Crown Square some time in 'company' days, so definitely before the summer of 1898. Both men are wearing waistcoats with metallic buttons and sleeves of a lighter-coloured material than the main body, along with kepi-style caps. Photo courtesy of the Glynn Waite Collection.

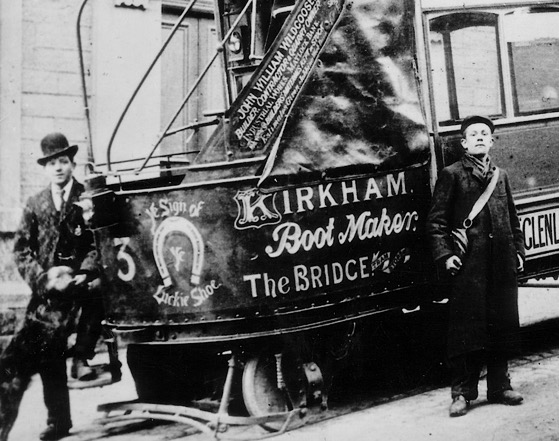

Tramcar No 3, captured outside the depot in 1898, shortly after being repainted with the title of the new owner, Matlock Urban District Council. Photo courtesy of the Glynn Waite Collection.

A blow-up of the above photo showing the youthful-looking conductor (right), and an individual of barely more advanced years, who stands with his foot rather proprietorially on the vehicle footstep, and who is probably the driver; both men are wearing informal attire, the conductor in a flat cap and the driver in a bowler hat. Given that the council had only just taken over the system, this would suggest that its predecessor — The Matlock Cable Tramway Company Limited — may not have bothered ordering new uniforms towards the end of its tenure.

A driver at the controls of Tramcar No 3 in Smedley Street loop, in either 1901 or 1902, clearly wearing a uniform and cap. Photo courtesy of the Glynn Waite Collection.

A blow-up of the above photo showing the driver's smart uniform: jacket, waistcoat, white shirt and tie, and kepi-style cap. The latter clearly bears a number — in this case '3' — though the use of these was apparently only short lived.

Another shot taken at Smedley Street loop, this time of Tramcar No 2, and probably in 1904. The driver is wearing his long-sleeved waistcoat without a jacket, so it was perhaps, a hot summer's day. Photo courtesy of the Glynn Waite Collection.

A rare survivor, two extremely young lads captured for posterity inside the depot, the subject on the right very probably one of the conductors — photo undated, but likely mid-Edwardian given the kepi-style cap. Photo courtesy of the Glynn Waite Collection.

Tramcar No 1 pictured outside the depot in what appears to be fairly recently outshopped condition (1904 livery), strongly suggesting that the photo was taken in that year. Photo courtesy of the Glynn Waite Collection.

A blow-up of the above photo showing the crew, both in kepis devoid of employee numbers, which had presumably fallen out of use by this time.

A poor quality photograph, damaged with age, but a rare one depicting the consequences of three-car working at Crown Square — photo undated, but certainly taken some time between 1904 and 1907. The conductor on the left is Wilf Swift, whose regular job was 'route & boiler man', but who was called on to turn out as a conductor during three-car working; he would have been working on the car immediately behind the one pictured, but would have been helping the conductor of this car, who is pictured holding a fare collection box, get the vehicle turned and loaded. The driver is Bill Handley; both he and the conductors are smartly turned out. Photo courtesy of the Glynn Waite Collection.

The crew of a somewhat faded-looking Tramcar No 2 pose for the cameraman outside the depot circa 1910. By this time, the kepi caps had clearly been superseded by more modern military-style caps with tensioned crowns (tops). Photo courtesy of the Glynn Waite Collection.

A blow-up of the above photo showing the conductor; although he has a new style of cap, the council were still clearly happy for them to be devoid of any formal identification such as a grade badge. The reflective strip is in fact the cap's chinstrap; these were in effect decorative and were worn across the top of the peak rather than under the chin, as seen here.

One of those rare photographs which can be very precisely dated, in this case, to the 18th January 1921. The driver — Bill Handley — is wearing a flat cap and greatcoat, which he presumably had to purchase himself, given that the Council stopped providing the latter garments during the Great War. Photo courtesy of the Glynn Waite Collection.

Driver Harry Wheldon aboard the platform of Tramcar No 3 — circa 1926. Unlike several other contemporary photos, he is clearly wearing a uniform and cap. Photo courtesy of the Glynn Waite Collection.

A postcard taken in the 1920s, in which both the conductor and driver appear to be wearing informal attire with flat caps, though this is far from conclusive. Photo courtesy of the Glynn Waite Collection.