City of Lincoln Tramways / Lincoln Corporation Tramways

History

Lincoln's standard-gauge, electric tramway, which was owned and operated by Lincoln Corporation, opened on the 23rd November 1905.

The electric tramway had a rather prolonged gestation, the corporation first expressing an interest in building a municipal system in 1899. Although they obtained powers to build and operate a series of lines in 1900, including acquisition and conversion of the existing horse tramway, which was owned by the Lincoln Tramways Company, there then followed an inordinately long period of indecision around which lines to build, and in particular, what form of current collection to use. Given Lincoln's narrow streets and historic buildings, it is perhaps no surprise that many in the city (and on the council) were wholly against the idea of overhead wires on the grounds of civic disfigurement.

Lincoln was in fact far from alone in its desire to modernise without having to have its streets festooned with overhead wires, many other towns grappling with the same dilemma at this time. By January 1904, the corporation had resigned itself to using overhead electric current collection, presumably having baulked at the price of a conduit system, and being unwilling to accept the risk inherent in using one of the new and largely untested surface-contact systems. However, around the same time, word reached the council of the Griffiths-Bedell surface contact system — manufactured by Wm Griffiths and Company Ltd of Ilford — so they promptly despatched the municipal electrical engineer to investigate. The council evidently liked what they heard, and in April that year, they formally decided to adopt the system for their new electric tramway, the only tramway in the British Isles to use this system on a permanent (rather than experimental) basis.

The council now concluded negotiations with the Lincoln Tramways Company, taking possession of the horse tramway in July 1904. Unfortunately for the corporation, Wm Griffiths & Co were not in a position to make a start on converting the tramway, the corporation having to operate the horse tramway for around a year, before it was closed for reconstruction on the 22nd July 1905. Work had already started on the new standard gauge line when it was pointed out to the council that they only had powers to construct a 3ft 6ins-gauge tramway, so the corporation presumably had to make a hurried and unplanned application to the Board of Trade for dispensation to use the larger gauge.

The Griffiths-Bedell system was one of the better-designed surface-contact systems, being cheaper to install and less prone, though not immune, to leaving the electric contact studs 'live' in the roadway after the passage of the tramcar. It did however suffer from other problems, in particular, the tendency of the magnetised skate underneath the tramcar to pick up all manner of ferrous detritus from the roadway (e.g., horseshoe nails), which would eventually lead to a short that would trip the main circuit breakers at the power station, stopping the whole tramway. Another more dangerous issue, and one which was no doubt a surprise to all, was the leakage of sewer gases into the electric cabling conduit beneath the roadway; electric arcing from tramway operation inevitably ignitied the gas (presumably methane), producing explosions of varying severity, the more spectacular sending cast iron inspection covers flying through the air. This issue clearly posed a significant danger to life and limb, but it was fortunately resolved by the simply expediency of blowing air through the cabling conduit each day before operations began.

The Lincoln system was one of the smallest electric tramways in the British Isles, running just 1.84 miles from a terminus at St Benedict's Square just short of the River Witham, southwards along High St, St Catherines and Newark Rd to just beyond the junction with Maple St at Bracebridge. Although various plans were made for lines on the north side of the River Witham, none were ever built. The system was in fact the second shortest municipal tramway system in the British Isles, only Barking Town Urban District Tramways being shorter at 1.6 miles.

Although very short, the tramway also had to negotiate two railway level crossings, which not only played havoc with the timetable, but also required a degree of coordination and timing between the motorman and conductor, to ensure that the tram could coast across the railway — there being no contact studs until the opposite side was reached — without the skate snagging the railway lines in the process.

Despite these trials and tribulations, the tramway carried healthy numbers of passengers, and appears to have been reasonably profitable, even though it never operated on Sundays. The corporation made improvements to the tram fleet, for example, fitting top covers, and continued to toy with the idea of extending the system, though by 1914 it seems to have finally given up on the idea in favour of introducing motorbus services. Any plans it had in this direction were however firmly placed in abeyance by the Great War, which also took a heavy toll on the system, with loss of men (and skills) to the armed forces, and severe restrictions on the sourcing of spares, track or new vehicles. As a result, the system emerged from the conflict in badly run-down condition, with the surface-contact system being in particularly bad shape, many studs having been replaced by wooden dummies, leading to instances of cars having to be pushed to the next 'live' one if for some reason the tram had had to stop over a dead stud. The corporation had in fact already decided — on the 18th February 1918 — to convert the system to overhead electric traction, government approval coming on the 24th March 1919.

The conversion was completed by the 26th December 1919, the corporation's attention then being diverted to the purchase of new motorbuses, the first of eleven vehicles being deployed on new services within the city on the 19th November 1920. Motorbus services were steadily expanded throughout the 1920s, and in 1926, they were introduced over the tramway, but only on Sundays when the trams of course, did not run. This move undoubtedly heralded the beginning of the end for the tramway, it being only a matter of time before significant expenditure (for example on track replacement) would see the trams replaced by motorbuses.

The decision to close the tramway was taken in August 1928, the last tram running in the afternoon of the 4th March 1929, later services being operated by newly purchased motorbuses.

Uniforms

Following its purchase of the Lincoln Tramways Company in July 1904, Lincoln Corporation continued to operate horse trams for just over a year, until 22nd July 1905. The take-over appears to have had no visible effect on the staff, their attire, or the tramcars themselves; the former continued to wear the informal heavy-duty working attire (jackets, overcoats, bowler hats and flat caps) that they had worn under company ownership (see link), and the latter continued to be largely festooned with advertisements, with no evidence presented in respect of who actually owned them.

For the inauguration of electrically-operated services, motormen and conductors were issued with double-breasted, 'lancer-style' tunics with five pairs of buttons (narrowing from top to bottom — see link), upright collars and epaulettes (with button fastening); the upright collars bore 'L C T' in individual metal letters on the bearer's left-hand side, and an employee number (probably) on the right-hand side. Caps were military in style with a glossy peak and tensioned crown (top); they bore a large scalloped-topped municipal shield badge (taken from the arms of Lincoln), which was worn above a standard 'off-the-shelf', script-lettering grade badge, either Motorman or Conductor. It is likely that the insignia were brass initially, subsequently being changed to nickel.

Tramcar crews were also issued with heavy, double-breasted, 'lancer-style' greatcoats with five pairs of buttons and high fold-over collars; the latter were reinforced in leather in the early days, and bore an employee number on both sides (in individual numerals). In later years, a switch was made to a greatcoat design with parallel buttons; these bore system initials on one collar, and an employee number on the other.

Inspectors probably wore single-breasted jackets edged in a finer material than the main jacket, with hidden buttons (or more likely a hook and eye affair) and upright collars; the trousers bore a stripe, again in a finer material than the main cloth. Each jacket collar carried embroidered script lettering, almost certainly the bearer's grade, Inspector. Caps were military in style with a tensioned crown, and appear to have borne an embroidered cloth cap badge in the form of the Lincoln shield, supplemented with a ribbon underneath. Perhaps surprisingly for such a small system, the LCT appears to have employed the services of a Chief Inspector; his uniform was very similar to those worn by inspectors, differing only in respect of the grade on the collars, and the use of braiding on the cap.

As with many tramway systems, female staff were employed during the Great War to replace men lost to the armed services; in Lincoln's case, these ladies were employed both as conductresses and motorwomen. Female staff were issued with long, tailored, single-breasted jackets with a row of five buttons, high fold-over collars and epaulettes; the jackets were sometimes worn unbuttoned, giving the impression of lapels. The collars carried an employee number on the bearer's left-hand side, and individual nickel 'L C T' initials on the right; a long matching skirt was also worn. Headgear was initially the same style of military cap issued to the men, though this appears to have been superseded by a baggy peaked cap, specifically for use by the ladies, probably in 1918 or 1919. Both types of cap bore script-lettering grade badges — either Motorman or Conductor — and sometimes, but not always, the standard municipal shield badge. Female tramcar staff were also issued with heavy, single-breasted greatcoats with five buttons, high fold-over collars and epaulettes. The collars appear to have been devoid of insignia.

Unlike most tramway operators, Lincoln continued to employ women tramcar staff well beyond the end of the war, in fact, right up until closure of the system in 1929.

Further reading

For a history of Lincoln's tramways, see: 'The Tramways of the City of Lincoln' by D H Yarnell, in the Tramway Review, Nos 63 (p163-173), 64 (p195-205) and 65 (p1926); Light Railway Transport League (1970 and 1971).

Images

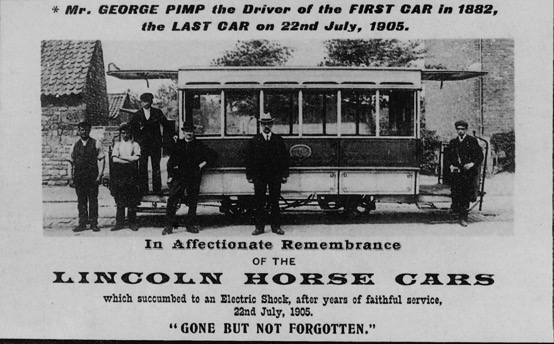

Horse tram drivers and conductors

A commemorative postcard of what appears to be Horsecar No 8 (purchased in 1889), and almost certainly taken in 1905 as the man in the centre is thought to be Stanley Clegg, Lincoln's Electrical Engineer. All present are wearing workman-like attire, with no evidence of badges or licences. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society, with thanks to David Voice.

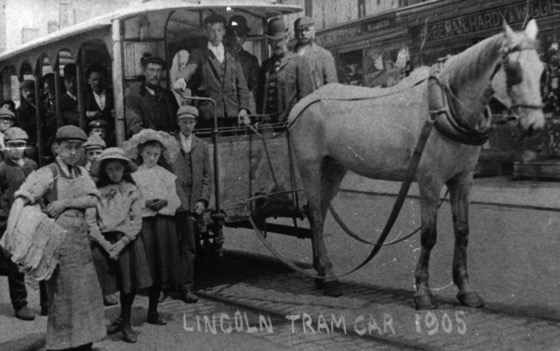

Horsecar No 3 in the vicinity of St Mark's Station with a service to Bracebridge. This photo was used as a postcard, being overprinted with "Last Journey Lincoln Horse Trams — 22nd July 1905"; however, it is entirely possible that the photo was taken somewhat earlier, and that its use as a commemorative postcard was an opportunity the postcard publisher judged too good to miss, irrespective of whether or not they actually possessed a photo of the 'last tram'! Photo courtesy courtesy of the National Tramway Museum.

A blow-up of the above photo showing the youthful-looking conductor (with cash-bag strap evident) and the driver. Both men are wearing informal attire.

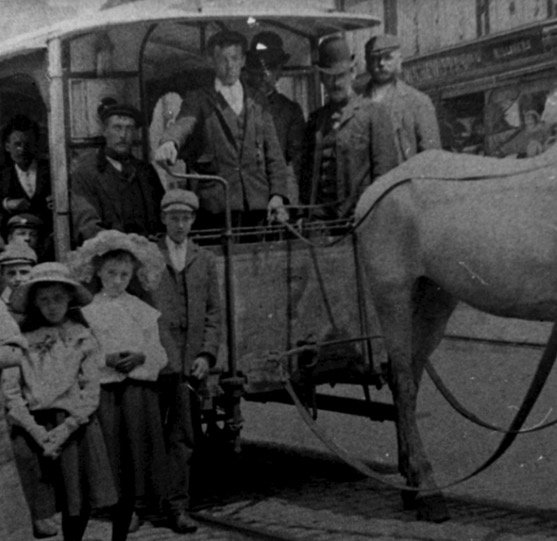

Another shot of the same horsecar (No 3) at the same location as the preceding photo — photo undated, but probably taken in 1905. Photo courtesy courtesy of the National Tramway Museum.

A blow-up of the above photo showing the conductor, the same boy as in the preceding photo.

Horsecar No 7 in St Benedict's Square at the city terminus — photo dated 1905, though some of the bowler hats on show, with upturned brims, look fairly anachronistic for that date, so possibly taken earlier. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society, with thanks to David Voice.

A blow-up of the above photo. Although it is unclear who is actually who, i.e., crew or passenger, all are clearly in everyday working attire rather than uniforms. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society, with thanks to David Voice.

An unidentified horsecar standing outside the Gate House Hotel at Bracebridge — the photo purportedly depicts the 'last horse tram', which if true, would date the photo to June/July 1905. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society, with thanks to David Voice.

A blow-up of the above photo, which reveals the driver to be wearing a heavy overcoat and a bowler hat.

Lincoln Horsecar No 5 at Bracebridge — photo purportedly taken in 1905. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society, with thanks to David Voice.

A blow-up of the above photo, which suggests that the conductor (far right) has a circular object on his jacket breast pocket, which could easily be mistaken for a licence; however, given that this is not seen in any other photo, it seems somewhat unlikely.

Motormen and conductors

What would appear to be a virtually brand-new Tramcar No 2, dating the photo to 1905 or 1906. Photo courtesy courtesy of the National Tramway Museum.

A blow-up of the above photo showing the conductor. He is wearing a 'lancer-style' tunic with epaulettes, along with a cap bearing a script-lettering Conductor grade badge, and a large municipal shield badge above it.

Lincoln Corporation Tramways scalloped shield cap badge — nickel. This badge is 37 mm from top to bottom (in the middle), which appears to be about the right size for the badges seen in the photographs. This pattern of badge was possibly used by all Lincoln's municipal services, including the Police and Fire Departments. Author's Collection.

Standard, 'off-the-shelf', script-lettering grade badges of the type used by the Lincoln Corporation Tramways — nickel. Author's Collection.

The crew of what looks to be a newly top-covered Tramcar No 5, dating the photograph to 1907/8. Author's Collection.

A blow-up of the above photo showing the conductor — Employee No 5 — who is wearing a script-lettering Conductor grade badge with a large municipal 'shield' badge above it.

Another blow-up of the photo above, this time showing the motorman, who is wearing a script-lettering Motorman grade badge and a municipal 'shield' badge.

A conductor and a motorman pose with Tramcar No 6 on a service for St Benedict's Square — photo dated 1910. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society, with thanks to David Voice.

A blow-up of the above photo showing the conductor and motorman, both in greatcoats.

A superb studio portrait of Great War conductress Mary Jane Jackson and her motorman brother-in-law, George Gregory (Employee No 2). Original held in a private collection, courtesy of the National Tramway Museum.

Although Conductress Jackson is wearing the usual LCT cap badge, Motorman Gregory has a Lincolnshire Regiment cap badge, the wearing of regimental badges being common practice at this time.

Lincoln Corporation Tramways collar initials — nickel. Author's Collection.

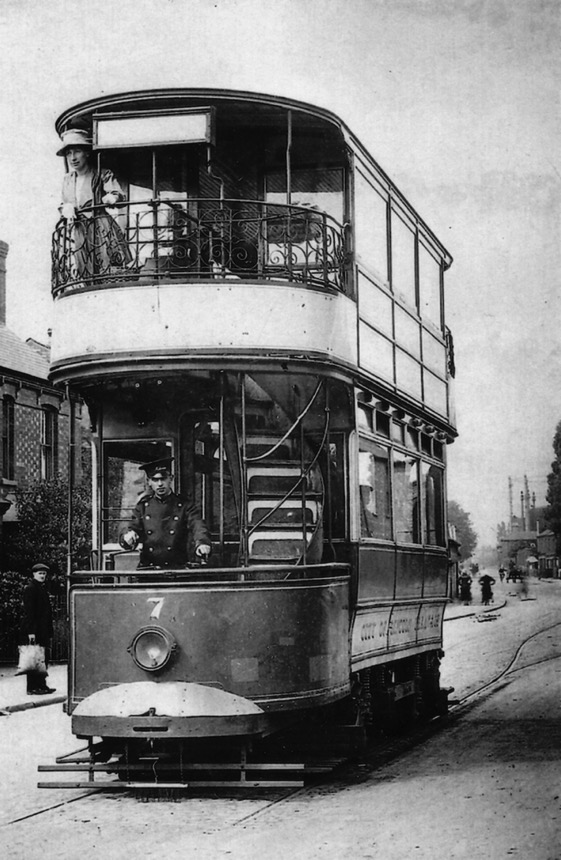

Motorman William Kirk at the controls of Tramcar No 7 — photo believed to have been taken in 1919. The tramcar is equipped for surface-contact working, with the brush for detecting 'live' studs clearly visible at the front of the vehicle; a brush was located at each end of the vehicle, but only the rear one was used, any studs which remained 'live' tripping a switch in the tramcar. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society, with thanks to David Voice.

A blow-up of the above photo; although the usual shield cap badge is not evident, it is probably present, but in shadow. The convex device at the front of the vehicle was to stop urchins riding on the fender! Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society, with thanks to David Voice.

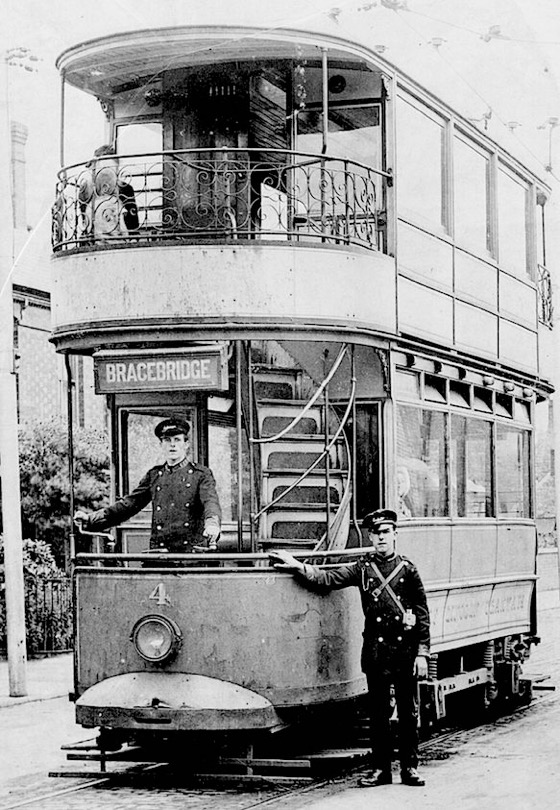

A motorman and a conductor pose with Tramcar No 4 — photo undated, but certainly taken after 1919 as the car is equipped for overhead line working. Photo courtesy of the National Tramway Museum.

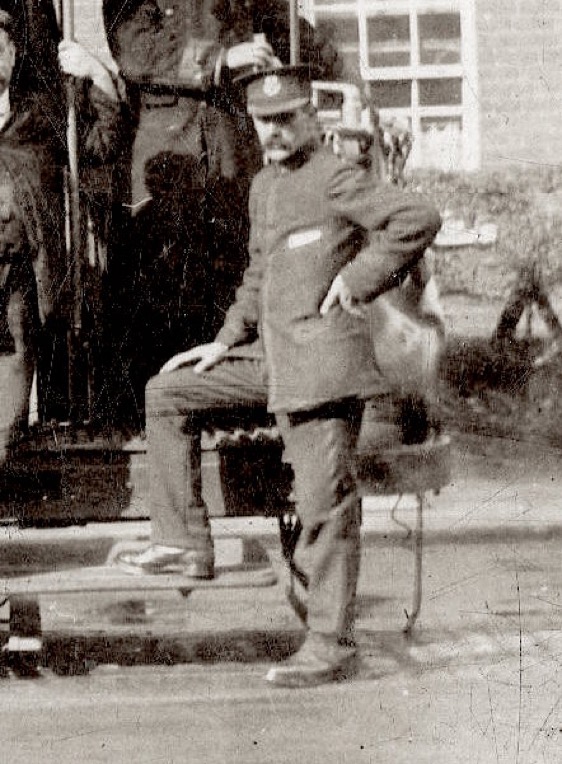

A blow-up of the above photo showing the motorman. The 'L C T' collar initials are easily made out.

Lincoln ‘shield’ badge — nickel. This badge is only 28 mm from top to bottom, which is too small to have been the badge seen in the photos. It was very probably used by Lincoln City Police as a collar or epaulette badge. Author's Collection.

Senior staff

A decorated English Electric tram (either No 7 or No 8) standing in the depot yard — photo undated, but possibly taken shortly after the Great War. Author's Collection.

A blow-up of the above photo, which is the only image I've been able to find of a Lincoln City Tramways inspector (assuming of course that he's not a Chief Inspector). The cap bears a large shield badge, with a ribbon underneath, probably of embroidered cloth.

A photograph of an individual who, in view of the two-line embroidered collar designations, is almost certainly a Chief Inspector, possibly Mr E H Curtis. The cap badge comprises the Lincoln shield with a ribbon underneath, and was probably made of cloth and bullion wire.

Lincoln inspector's cap badge — cloth. This was certainly worn during the later bus era, and there remains a possibility that it may have been worn towards the end of the tramway's life. Author's Collection.

Female staff

Great War conductress Mary Jane Jackson in her tailored, single-breasted jacket and military-style cap. Original held in a private collection, courtesy of the National Tramway Museum.

Another shot taken at Bracebridge, this time of Tram No 1 — photo dated 1918. The conductress is believed to be Jane Whitworth. Photo courtesy of the National Tramway Museum.

A blow-up of the above photo showing the motorwoman, believed to be Annie 'Nancy' Scott (possibly Employee No 2). The large size of her cap badge is very noticeable in this shot.

An all-female crew pose with their vehicle (Tramcar No 2) at Bracebridge — photo undated, but almost certainly taken at the end of, or very shortly after the Great War (the vehicle is still equipped for stud working). Photo courtesy of the National Tramway Museum.

A blow-up of the above photo showing the crew. Whilst both ladies are wearing script-lettering cap badges, only the conductress appears to have a shield badge above. Both caps are baggy, rather than the standard military issue, and were presumably intended for female staff only.

Lincoln Corporation Tramways scalloped shield cap badge — nickel. This badge is 37 mm from top to bottom, but with a pin back rather than lugs. This is an unusual fixing for a tramway badge, but one which may have seen use on female headwear from the Great War onwards (see later). Author's Collection.

Motorwoman Annie 'Nancy' Scott again, this time at the controls a very dilapidated Tramcar No 10 at St Catherine's Grove, as supplied in a grey primer — photo dated July 1920, i.e., after the conversion to overhead working. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society, with thanks to David Voice.

A blow-up of the above photo showing Motorwomen N Scott, who appears to be wearing a baggy cap. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society, with thanks to David Voice.

Lincoln City Tramways conductress — 2nd March 1929. The usual script-lettering grade badge is absent, and the cap is of a baggy style rather than the earlier military-style. Photographer, H Nicol, with thanks to the National Tramway Museum.