Dublin and Blessington Steam Tramway

History

The story of the Dublin and Blessington Steam Tramway, which plied between Dublin and the County Wicklow town of Blessington, some 15 miles away to the southwest, commenced as far back as 1880. On the 11th November that year, a group of promoters secured approval — in the form of the Dublin and Blessington Steam Tramway Order, 1880 — to build a 3ft-gauge steam tramway between Terenure, on the outskirts of Dublin, and Blessington. They had wanted to use steam power between Terenure and Nelson Pillar in Dublin, over the tracks of the Dublin Tramways Company, but could not overcome the objections of the city council to this mode of traction. The promoters probably struggled to raise the capital to build the line, as they had to go to the expense of securing an extension to the time allowed for construction, which was two years from order date, i.e., 11th November 1883. Approval was granted on the 16th March 1883 — via the Dublin and Blessington Steam Tramway (Extension of Time) Order, 1883 — to push the completion date back to the 11th November 1884. It is unclear what happened next, but no work was done in respect of construction, so the powers probably lapsed in 1884.

By 1887, the scheme had been revived, this time under the auspices of the Dublin and Blessington Steam Tramway Company, which was constituted by an order of the Privy Council on the 23rd July 1887. This may have been at the same time that a new order was granted — the Dublin and Blessington Steam Tramway Order, 1887 — for the construction of a 15.5-mile tramway between Terenure and Blessington, but to the Irish Standard Gauge of 5ft 3ins. This presumably included the original running powers into central Dublin (3.25 miles) over the tracks of the existing horse tramway, now owned by the Dublin United Tramways Company.

The company quickly issued a prospectus, promising rich pickings (7-10% annual dividends), which utterly failed to materialise. Importantly, £40,000 of the stock came with baronial guarantees, which would have consequences for the company and the baronies in later years. Baronial guarantees were peculiar to Ireland, and effectively guaranteed payment of a dividend (in this case 5% per annum), which would then be repaid by the tramway company from its profits, assuming any were made; if not, the money came from within the baronies themselves, i.e., from local rate payers.

The line opened for business on the 1st August 1888 and was essentially a roadside railway with some street running. The locomotives and trailers were, however, pure tramway, though the former (six Falcon engines) were somewhat underpowered for the loads that were carried (often several trailers and goods vans), especially up the steep incline between Embankment and Crooksling. Loadings were good, such that in 1889, a new company was formed — the Blessington and Poulaphouca Steam Tramway Company — to build an extension to the tramway to the well-known beauty spot at Poulaphouca. Investors do not seem to have been particularly enthusiastic, as the line did not open until the 1st May 1895. Operation was leased to the D&BSTCo, through services commencing in 1896.

This took the Dublin and Blessington Steam Tramway operation to its final extent of 19.6 miles. From Terenure, where the main depot was located, the line ran broadly southwestwards through Templeogue, Tallaght, Clondalkin Road, Jobstown, Embankment, Crooksling, Brittas, The Lamb, Tinode and Cross Chapel, to Blessington; thereafter, the tracks of the B&PSTCo continued to Poulaphouca via Ballymore Road.

Although the D&BSTCo had hoped to run passenger services into central Dublin, the corporation's objection to steam traction precluded these. This did not, however, preclude the DUTCo, whose tracks were physically connected to those of the D&BSTCo at Terenure, from running electrically hauled night-time goods services between the two systems between 1909 and 1927.

A larger engine was procured in 1892 from Thomas Green and Sons of Leeds, which was a staggering three times heavier than the six original Falcon engines. Although this engine was able to cope with the loads, it was far too heavy for the track, with fairly predictable consequences, so did not last long. Further locos were obtained in subsequent years, and one of the original Falcon engines was completely rebuilt. One unusual aspect of the majority of the later engines was that they had two cabs, so could be driven from either end, as there were no turning facilities. With increasing costs and falling passenger numbers, two petrol-electric trams were tried (rather unsuccessfully) in the Great War, as well as a Drewry and two Ford-powered railcars in the 1920s.

The tramway had an unenviable safety record, many accidents involving fatal collisions with pedestrians, not to mention a conductor being flung from a swaying trailer to his death. These events earned it the sobriquet of "Ireland's longest graveyard".

In 1911, the company developed an ambitious plan to electrify around half the line, though where it was to obtain the capital from is anyone's guess. However, before this could be put to the test, the Great War intervened, and the plans were dropped. By the early 1920s, the tramway was in serious trouble, with passenger numbers dropping and freight switching from the tramway to lorries. It had in fact never been a particularly prosperous concern, the profits made never being sufficient to pay a dividend to the ordinary shareholders. The preference shares holders on the other hand, who had the baronial guarantees, continued to be paid a dividend, the shortfall coming from the local rates. As the company's small profits turned into ever-bigger losses, the burden on the rate payers grew, as did the clamour for something to be done. Attempts to include the tramway in the formation of Irish Railways fell on deaf ears, as did approaches to just about everyone and anyone who might have had the slightest interest in taking the tramway over.

The B&PSTCo finally threw in the towel in early 1927, services over their tracks ceasing on the 30th September 1927. By this time, the County Councils of Dublin and Wicklow — in whose areas the baronies lay — had clearly had enough, and petitioned the Irish Minister for Industry and Commerce to transfer the enterprise to them, which was within his power should the tramway make a loss in four consecutive half years, a situation that had pertained since 1914/15. The application was duly granted on the 1st December 1927 — under the Dublin and Blessington Steam Tramways (Committee of Management) Order, 1927 — the councils formally taking ownership on the 1st January 1928.

The councils could do little to revive the tramway's fortunes, which were made even worse by the appearance of motorbus competition in 1929, in the form of the Paragon Omnibus Company, whose services did not involve a change of vehicle at Terenure. With no prospect of curtailing the losses, and with no-one interested in taking over the tramway, the only option was closure. Approval to close the tramway was granted on the 22nd July 1932 via the Dublin and Blessington Steam Tramway (Abandonment Act), the last tram running on the 31st December 1932.

Uniforms

In common with most steam tram operations, drivers wore railway footplate-like attire comprising: cotton jackets, heavy trousers and cloth caps (flat, cotton or cloth); neither the caps nor the jackets carried insignia of any description, including licence badges. Like its near neighbour, the Dublin and Lucan Steam Tramway (see link), the D&BST seems to have treated its steam tram engines as locomotives, always operating them with two men, a driver and a stoker/fireman; the latter essentially wore very similar attire to the drivers.

Good quality photographs of conductors are unfortunately rare, with just a small number of examples having survived, and all taken after the Great War. By this time, conductors were certainly wearing single-breasted jackets with lapels, along with a company-issued kepi-style cap. Although it is currently unclear whether the uniform jackets carried metal buttons, the caps were most certainly marked, bearing a prominent cap badge, with letters/numerals mounted on an open frame; an example is, however, yet to come to light, so the precise form and lettering remains unknown. Conductors were also issued with long, double-breasted greatcoats with lapels; these were devoid of insignia, but did bear metal buttons.

The D&BSTCo introduced petrol-electric railcars in 1915 and petrol railcars in the 1925, in a forlorn attempt to stave off motorbus competition. Drivers appear to have taken the opportunity that driving a much cleaner vehicle presented, to wear smart though still informal attire.

It is believed, though it is not absolutely certain, that the D&BSTCo did not use the services of travelling inspectors, instead following small railway company practice, relying on conductors and station masters. Like most if not all systems in Ireland, female staff do not appear to have been employed during the Great War.

Further reading

For a short history of this tramway, see: 'The Dublin and Blessington Tramway' by H Fayle and A T Newham (Locomotion Papers No 20); The Oakwood Press (1963). For an overview of the Irish tram scene, including the Dublin and Blessington, see 'Irish Trams' by James Kilroy; Colourpoint Books (1996).

Images

Steam tram drivers and conductors

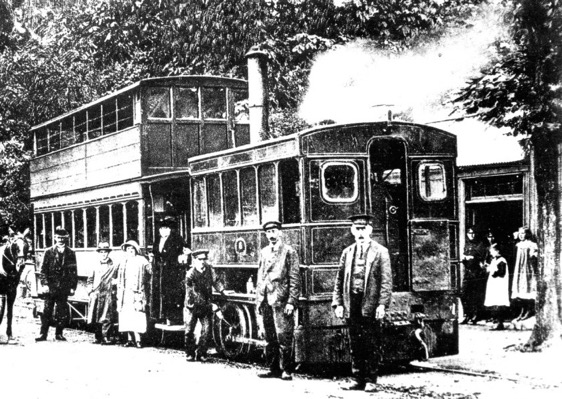

A superb photograph of D&BSTCo Steam Tram No 6 (a Falcon product) in original condition (though without skirts), before it was completely rebuilt as a tank locomotive in 1914 — photo purportedly taken in 1887, though it is possibly taken somewhat later. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society, with thanks to David Voice.

An enlargement of the above photograph showing the portly gentleman on the right, who is almost certainly the driver. Despite the grubby nature of the job, he is still quite smartly turned out in polished shoes, a waistcoat, light-coloured cotton jacket, and what looks to be a soft-topped cap (without a badge).

Another blow-up of the above photograph, this time showing the younger man on the left, who is probably the stoker/fireman. His attire, including his close-fitting flat cap, is considerably grimier than his colleague's, probably reflecting the fact that he did all the dirty heavy work!

No 6 again, but this time in post-1914 guise, complete with glazing, which must have been somewhat challenging to keep clean — photo undated, but probably taken during or shortly after the Great War. The individual with oil can in hand is probably the stoker/fireman, with the driver second from right, and a rather proprietorial-looking gentleman (first right) who is in all probability a station master. Photo courtesy of Jim Kilroy, tram archivist at the National Transport Museum (see link).

A rare photograph of a D&BSTCo conductor, which judging by the look on the latter's face, and the fact that all the passengers appear not to have noticed the photographer, was probably a spur of the moment shot. The photograph, which has perfectly captured a 'moment in time', is believed to have been taken at the Terenure terminus (my thanks to David Walsh for the identification); judging from the fashions on display, it was probably taken in the late 1920s or early 1930s. Photo courtesy of Jim Kilroy, tram archivist at the National Transport Museum.

An enlargement of the above photograph showing details of the conductor's uniform. He is wearing a kepi-style cap, which would have been considered quite old-fashioned by this time, and which clearly bears a large cap badge; it appears to be voided (i.e., open backed), with letters/numbers mounted upon a frame. Unfortunately, an example is yet to come to light, so the lettering remains unknown.

A photograph taken on 10th February 1932 (in the last year of operation) at what is probably Embankment. The engine is No 10 (formerly No 2), a curious, double-ended Thomas Green & Sons product. Photo courtesy of David Gladwin, with thanks to Trevor Preece.

An enlargement of the above photograph showing the smartly dressed conductor, in single-breasted jacket with lapels and kepi-style cap. It is not beyond the bounds of possibility that he is the same individual depicted in the previous photograph.

Railcar drivers and conductors

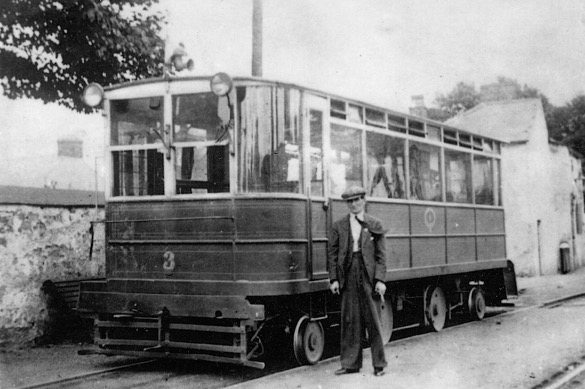

A photograph taken towards the end of the tramway's life (late 1920s or early 1930s) at Templeogue depot, showing No 3, a petrol-powered railcar. Photo courtesy of Jim Kilroy, tram archivist at the National Transport Museum.

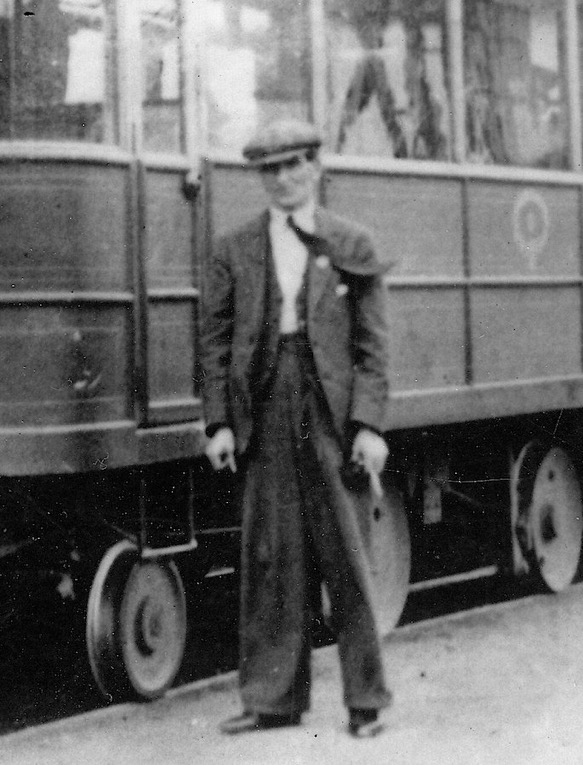

An enlargement of the above photograph showing the driver, smartly dressed, though clearly in informal attire, topped off with a flat cap.