Rossendale Valley Tramways

History

Powers to build a steam tramway connecting Rochdale, Whitworth, Facit, Rawtenstall and Holmefield were granted as early as 1882, under the Manchester, Bury and Rochdale Tramways (Extensions) Order. This was passed into law on the 12th July 1882 as part of the Tramways Orders Confirmation (No 3) Act, 1882. The promoters of the order were Bury, Rochdale and Oldham Steam Tramways Limited, the creation of an unscrupulous London businessman, Henry Osbourne O'Hagan, who together with his cronies was eventually ousted, though not before they had royally fleeced the unwitting shareholders (see link). Unfortunately, this left the company in a parlous state, from which it never really recovered.

After extending the time allowed for construction, the company, by this time restructured as the Manchester, Bury, Rochdale and Oldham Steam Tramways Company, eventually gave up hope of ever building its planned Rossendale Valley lines, having only reached as far as Facit. The remaining Rossendale lines were subsequently parcelled up into a separate undertaking, which was sold off to new promoters, some of whom were also involved with the MBR&OSTCo. On the 24th July 1888, the new promoters obtained powers to take over the planned lines, of which there were circa 8.22 miles (from Facit to Holmefield, just north of Rawtenstall) and to construct them to a gauge of 4ft 0ins rather the originally planned narrower gauge of 3ft 6ins. The powers, which were granted under the Rossendale Valley Tramways Act, 1888, also incorporated a new company to build and operate the lines, the Rossendale Valley Tramways Company.

Construction started in September 1888, with the first section — from Rawtenstall to Waterfoot — opening just over four months later on the 31st January 1889. In May/June, construction commenced on extending the tramway northwards (from Rawtenstall to Holmefield) and eastwards (from Waterfoot to Bacup); the new lines opened on the 2nd August, and the 8th August 1883, respectively.

Meanwhile, the company had applied for powers to extend the tramway, primarily northwards from Holmefield to Burnley (6.53 miles); these powers were granted on the 30th August 1889 under the Rossendale Valley Tramways (Burnley Extension) Act, 1889.

Construction of the northward extension, as far as Crawshawbooth, did not commence until April 1881, the new section opening to passengers five months later on the 12th September 1891. This took the system to its final size of 6.35 miles. The system was essentially a long single line with loops, commencing in Bacup at the junction of Bridge Street and Market Street, running westwards along Newchurch Road and Bacup Road through Waterbarn and Waterfoot to the Queens Arms in Rawtenstall, where it turned northwards along Bank Street, King Street and Burnley Road West, through Holmefield to a terminus just short of York Street in Crawshawbooth. There was also a short branch southwards along Bank Street to the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway Company's level crossing near to the station.

Although the RVTCo's tracks were physically connected to those of the Accrington Corporation Steam Tramways Company in Queens Square, Rawtenstall, both systems being the same gauge, regular through running was never instigated.

The company subsequently decided not to build the extension northwards from Crawshawbooth to Burnley, as well as that southwards from Bacup to Facit, the latter almost certainly because the MBR&OSTCo was keen to abandon its unremunerative line to the town. As a consequence, and presumably to get its deposits back, the company applied for powers to formally abandon these sections, these being granted on the 20th June 1892 under the Rossendale Valley Tramways (Abandonment) Act, 1892.

The system was initially operated by nine Thomas Green and Sons steam trams (delivered in 1888 and 1889), these being joined by two more in 1893 and 1894, and finally, in 1902, by two secondhand engines from Blackburn Corporation.

In July 1898, the British Electric Traction Company, which at this time was aggressively purchasing horse and steam-operated tramways across the British Isles with the intention of converting them to electric traction, acquired a majority interest in the RVTCo. The BETCo clearly had ambitious plans for a sizeable electric tramway network in northeast Lancashire, as the following year it struck an agreement with the neighbouring ACSTCo aimed at securing electrification of that company's lines in Accrington, Haslingden and Rawtenstall. Its plans were, however, frustrated by Accrington Corporation, which owned the tracks in Accrington (the ACSTCo operating them under a lease agreement), and which eventually decided to convert them to electric traction and operate the system itself.

Despite this setback, the BETCo, in the form of the RVTCo, duly acquired powers — on the 8th August 1902 — to electrify its lines in Rawtenstall and Bacup, and to build an extension northwards from Crawshawbooth to meet the tracks of Burnley Corporation Tramways, as well as an extension (also northwards) from Waterfoot to Water, in total 7 miles of new overhead electric tramway. These powers were granted on the 8th August 1902 under the Rossendale Valley Tramways Act, 1902. The BETCo presumably considered the prospect of electrification to be financially viable as the steam tramway was still carrying over 1.3 million passengers per year.

Importantly, however, the 1902 Act included a clause, presumably inserted at the insistence of Rawtenstall and Bacup Corporations, that should the company fail to convert the system within four years, then they would both have the right to buy the tramway. Without this clause they would not have had the right to buy it until 1909/1910, under the Tramways Act of 1870 (i.e., 21 years after the passing of the enabling acts).

The BETCo was initially hopeful, but serious disagreements between the corporations in respect of municipal versus company operation, led to an endless stalemate. As time wore on and the deadline when the corporations could purchase the undertaking in their respective areas approached — 1906 — the BETCo seems to have resigned itself to getting the best price it could and selling out to the corporations. The corporations duly acquired powers (on the 26th July 1907 under the Rawtenstall Corporation Act, 1907) to take over the tramway, convert it to electric traction, and operate it municipally.

The RVTCo was sold to Rawtenstall and Bacup Corporations on the 1st October 1908, the former from then on operating the aged steam system. That same month (some sources state on the 1st October whilst others state the 20th October), Rawtenstall Corporation also took over operation of the Queens Square to Lockgate section of the former ACSTCo, which it had owned since the 1st January 1908, but which had been leased to Haslingden Corporation.

The steam system was briefly expanded again on the 10th December 1908 when the steamers began providing a service over the newly constructed tramway between Crawshawbooth and Loveclough. The new electric system was partially opened on the 15th May 1909, the last steam service of all running on the 22nd July 1909.

Uniforms

In common with the vast majority of UK steam tramways, RVTCo drivers wore railway footplate-like attire, comprising heavy-duty cotton jackets and trousers, along with soft-topped or cloth caps; no badges of any kind were worn. Up until the mid-to-late 1890s, conductors wore smart but informal attire: jacket and trousers, shirt and tie, along with an overcoat. Headgear followed the fashion of the day, initially the bowler hat, but later on the flat cap. No insignia, including licence badges, appears to have been worn.

In the late 1890s, almost certainly following the take-over by the British Electric Traction Company in 1898, conductors were provided with double-breasted jackets (edged in a lighter material), with four pairs of buttons, three waist/hip-level pockets and lapels, together with matching trousers and soft-topped peaked caps. Neither the jackets nor the caps appear to have borne any insignia. In the mid-Edwardian era, the style of the jackets was altered, though they were still double-breasted with lapels; the soft-topped caps were also dispensed with, being superseded by tensioned-crown peaked caps, though still without a badge. The absence of insignia was not unusual for a BETCo system that had failed to be converted to electric traction, probably because the company liked to reserve its 'Magnet & Wheel' device, with its overt electric symbolism, for use on its electric tramways.

Surviving photographs show that inspectors were provided with single-breasted, three-quarter-length coats bearing four buttons and lapels, but without badges of any kind; like conductors' jackets, they were edged in material of a lighter colour than the main body. Their drooping-peak caps possibly bore a metal block-capital grade badge, 'INSPECTOR'.

Further reading

For a brief history of the RVTCo, see: 'A History of the British Steam Tram Volume 4' by David Gladwin; Adam Gordon (2008).

Images

Steam tram drivers and conductors

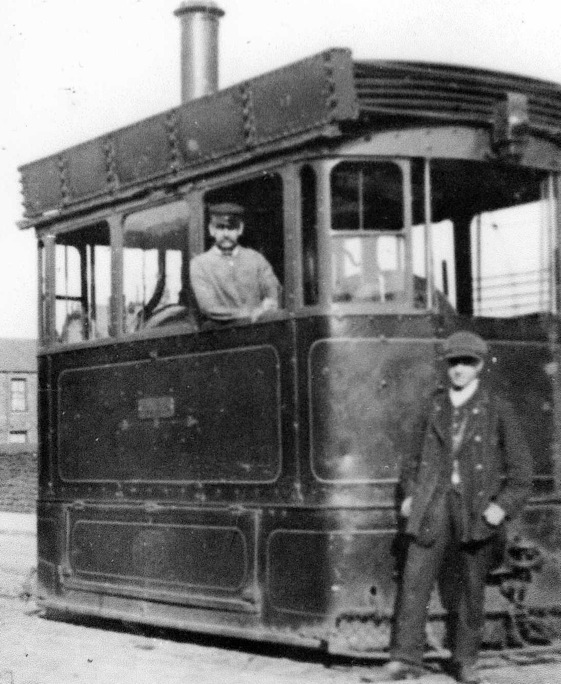

A brand-new Steam Tram No 3 (a Thomas Green and Sons product) and a newly delivered trailer— photo probably taken prior to opening, in either December 1888 or January 1889. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society.

An enlargement of the above photograph showing the driver and the two other officials. The driver is wearing typical railway footplate attire and a soft-topped peaked cap; no badges or licences are in evidence.

Rossendale Valley Tramways Company Steam Tram No 6 stands outside the Queens Arms, Rawtenstall, circa 1890. Photo courtesy of Duncan Holden.

An enlargement of the above photograph showing the conductor, in overcoat and flat cap, and the driver, in typical footplate attire.

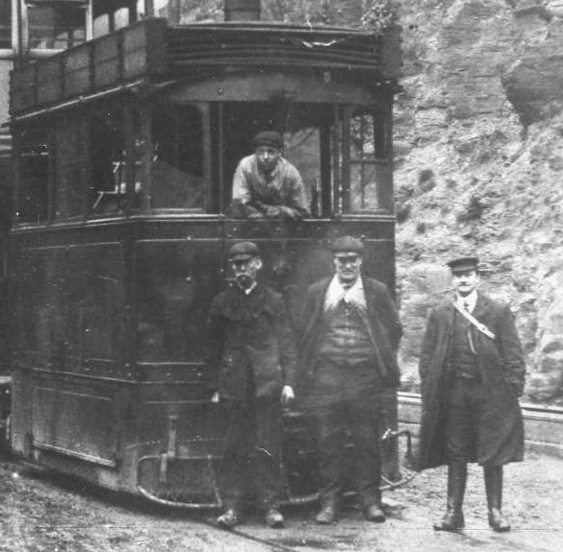

A group of four tramwaymen stand with an unidentified engine and trailer near Stacksteads — photo undated, but probably taken in the mid-to-late 1890s. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society.

An enlargement of the above photograph showing the tramwaymen; all bar the conductor are filthy, as is the roadway. The conductor is wearing informal attire along with a soft-topped peaked cap, all probably self-purchased.

The crew of an unidentified steam tram pose for the camera together with an inspector (in all likelihood) outside Glen Top Brewery, Stacksteads — photo undated, but probably taken around the turn of the century. The conductor (middle) is clearly wearing a uniform edged in a lighter material than the main garment, along with a soft-topped peaked cap. Neither the driver nor the conductor are wearing a cap badge, the bright spot on the driver's cap merely being a reflection. Author's Collection.

A rather poorly focused shot, but another image which shows a conductor in a double-breasted jacket edged in material of a lighter colour — photo undated, but probably early 20th Century. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society.

Steam Tram No 1 standing in Burnley Road, Crawshawbooth in 1907. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society.

An enlargement of the above photograph showing the conductor (Bill Dust), driver (Dick Walmsley) and an inspector. By this time, conductors were wearing a different style of double-breasted jacket, along with tensioned-crown peaked caps, everything however, still devoid of insignia.

Senior staff

Two RVTCo inspectors taken from the photos above. Both are wearing single-breasted, three-quarter-length coats bearing four buttons and lapels, along with drooping-peak caps. The photograph on the right certainly hints at an oblong, metal cap badge, possibly a grade badge. it is unclear whether the marks on the sleeves of the inspector in the first photograph are material stripes of just creases highlighted by the camera flash.