Potteries Electric Tramways

History

The Potteries Electric Traction Company was a subsidiary of the much larger British Electric Traction Company Ltd (BETCo), a concern which, over the course of its history, either owned, part-owned or leased almost 50 tramway concerns across the British Isles. The PETCo was expressly set up on the 18th June 1898 to manage the BETCo's interests in the Potteries, which essentially consisted of the North Staffordshire Steam Tramways Company, as well as various powers to build and operate electric tramways in the area.

The NSTCo had actually commenced conversion of its steam tramway to overhead electric traction in 1897, but before commencing electric working, it was formally taken over — on the 26th January 1899 — by the PETCo. Whilst the NSTCo was effectively now a subsidiary of the PETCo, a rather strange state of affairs existed whereby the NSTCo continued as the owning company (of the tramway), whilst the PETCo operated the system, paying rent to the NSTCo. This complex relationship was only resolved in March 1932 with the liquidation of the NSTCo, almost four years after the closure of the electric tramway.

Public electric services, which were initially operated by the NSTCo, commenced on the 16th May 1899, the last steam trams running in late June 1899. The PETCo formally took over operation of the system on the 21st November 1899.

Despite having to deal with the innumerable councils through whose bailiwicks the tramway ran, some of which attempted to extract as many lucrative concessions as possible from the tramway company, the system expanded rapidly through the first years of the 20th Century. At its maximum, the 4ft-gauge PETCo system extended to 31.73 miles, consisting of a dense network of lines running: eastwards from Stoke through Fenton to Longton, where the line split, one branch continuing southeastwards to Meir and the other southwards to Dresden; southwards from Stoke along London Rd, northwards along Glebe St, and to Newcastle-under-Lyme; westwards from Newcastle-under-Lyme to Silverdale, and northwards to Chesterton and Longport; northwards from Hanley to Sneyd Green, southeastwards to Fenton, southwards to Stoke, southwestwards to Newcastle-under-Lyme and northeastwards to Burslem; eastwards from Burslem to Smallthorne and northwards to Tunstall; and finally, eastwards from Longport to Burslem and northwards through Tunstall to Goldenhill.

The system was unusual in several regards, firstly by virtue of the number of local authorities it had to deal with (at one time 18), secondly, in running a large fleet which consisted entirely of single-deck vehicles (due to numerous low bridges), and lastly, for being one of a very small number of tramways that ran trailer cars. The company in fact started operations with 20 tramcars and 20 trailers, but services had hardly started running before the company took the decision to motorise the latter.

Traffic was heavy, which necessitated continuous additions to the fleet until 1908, as well as significant track doubling, most of the system consisting of single line and loop construction.

The company introduced its first bus feeder service on the 22nd December 1913, having unsuccessfully experimented with omnibuses in the Edwardian era, but soon faced bus competition itself (in the form of the Greater Omnibus Company Ltd). The Great War was however to alter everything, firstly through government requisition of vehicles, thereby putting paid to the competition, but also by enabling a large number of working men to learn how to drive, which was to have serious consequences for the tramway company in the 1920s.

The tramway, like many across the country, suffered the usual depredations of the Great War, with increased loadings, staff shortages, greatly reduced maintenance and an inability to source spares or new vehicles etc. By the end of the conflict, the tramway was in very run-down condition, with the track in a very poor state (it also suffered from mining subsidence) and most of its vehicles heading towards the end of their working lives. On top of this came unrestricted bus competition from private operators, with Stoke-on-Trent Corporation seemingly happy to licence anyone who applied, irrespective of whether they were running over the very tram routes which the corporation derived an income from (in the form of way-leave and rates). The company fought back with innovative measures of its own, such as twin-car sets, one-man-operated tramcars and through cars, but by the mid-1920s, the competition had reached such incredible heights that the tramway could not continue. To give some idea of the magnitude of the competition, in the six years between 1920 and 1926, passenger numbers fell by a staggering 20 million per annum from 30 million to 10 million.

With the company's appeals to Stoke-on-Trent Corporation (an amalgamation of six Potteries towns) having fallen on deaf ears, and significant costs in the offing in terms of renewals (track and vehicles), it had little choice but to abandon the tramway system. The company had clearly seen which way the wind was blowing and had had the foresight to acquire powers to replace the trams with buses, these being granted in 1923. Stoke Corporation were offered the system in 1925 but declined, effectively rubber-stamping the tramway's demise.

The first lines to close were Newcastle-under-Lyme to Chesterton and Silverdale, going on the 30th September 1926, the final tram on this large network running just 23 months later on the 11th July 1928.

Overall, the PETCo had operated very successfully until the 1920s, paying reasonable dividends up until 1922, after which it did not pay another. The NSTCo seems to have fared better, its arrangement with the PETCo ensuring that the latter paid all its interest charges, as well as a guaranteed minimum dividend of 5% (paid every year up until 1930), and a share in the profits.

Uniforms

Photos taken in the first year of electric operation indicate that motormen were initially issued with double-breasted jackets with four pairs of buttons and lapels; conductors on the other hand wore single-breasted jackets with five buttons and stand-up collars. The collars on both styles of jacket bore insignia of some kind, very probably system or company initials, which cannot unfortunately be made out on the surviving photographs. Caps were initially in a kepi-style with a glossy peak and bore an oval cap badge, more than likely of embroidered cloth, and possibly making use of the Staffordshire knot. It seems likely that these uniforms were issued by the NSTCo, as this company operated the system for the first 6 months of its existence, the PETCo not taking over until late November 1899. Documentary evidence indicates that motormen were initially employed by the PETCo, whilst conductors were employed by the NSTCo, an arrangement which presumably ended with the full take-over by the PETCo; it is unclear whether this difference was reflected in the uniforms.

At some point following the PETCo assuming responsibility for operation, a switch was made to a more standard style of BETCo uniform; although jackets appeared to vary somewhat between BETCo systems, as well as across the decades, the cap badges, collar designations and buttons usually followed a standard pattern.

Despite the PETCo's rather extensive system (over 30 route miles in total), photographs which include tramcar crews are not only of very poor quality, but almost always show motormen and conductors wearing greatcoats, which unfortunately obscure details of the uniforms worn underneath. A couple of images do however reveal that both motormen and conductors were issued with single-breasted jackets with five buttons (of the standard BETCo pattern — see link), two breast pockets (with button closures), epaulettes and stand-up collars. Although details of the collar insignia cannot be made out on the surviving photographs, by analogy with other BETCo systems, they probably carried system initials on the bearer's right-hand side, in individual letters (probably 'P E T'), and an employee number on the left-hand side, in individual numerals, all in brass. Caps were initially soft-topped with a glossy peak, and the standard brass BETCo ‘Magnet & Wheel’ issue. These were however quickly superseded by tensioned-crown peaked caps; these bore the standard brass BETCo 'Magnet & Wheel’ cap badge, but unlike other BETCo systems (excepting those run by the Birmingham and Midland Joint Tramways Committee), worn above brass system initials ('P E T') rather than an employee number.

Tramcar crews were also issued with double-breasted greatcoats with five pairs of buttons, high fold-over collars and epaulettes; neither the collars nor the epaulettes appear to have carried badges.

Inspectors wore single-breasted jackets without buttons (more than likely with hook and eye fasteners) and stand-up collars; the jackets were edged in a finer material than the main body, and the collars bore the grade — 'Inspector' — in embroidered script lettering. Photos from the early days of the system show that inspectors wore drooping-peak caps topped by a pom pom; the cap bore a large oval cloth cap badge with the bearer's grade in block capitals — 'INSPECTOR' — above which were the system initials in script lettering, 'PET'. At some point, the drooping-peak caps were replaced by tensioned-crown caps; these bore the standard 'Magnet & Wheel' cap badge worn above a hat band bearing the grade — 'Inspector' — in embroidered script lettering. The grade on the upright collars was also changed, quite unusually to a small one-piece grade badge — 'INSPECTOR' — very probably of metal; it is unclear when this change was made, and it remains a possibility that it was after the demise of the trams.

Although the vast majority of British Tramway systems employed women during the Great War, to replace male staff lost to the armed services, the situation with the PETCo remains unclear, with neither photographic nor documentary evidence available.

Further reading

For a history of the system, see: 'The Tramways of the Potteries' by David Voice; Adam Gordon Publishing (2018) and 'Tramways in the Potteries and North Staffordshire, Part 2' by Harry Dibdin, in the Tramway Review No 27 (p66-87); Light Railway Transport League (1960).

Images

Motormen and conductors

A new-looking Tramcar No 64 posed for the cameraman with its crew — photo undated, but probably taken not long after its delivery in 1899/1900, and certainly no later than 1902 when it was extensively rebuilt. Both men are wearing identical kepi-style caps, but different styles of jacket. Source unknown.

A blow-up of the above photo showing the conductor. His kepi-style cap does not bear a BETCo cap badge and nor do his collars, suggesting that the badges may have been NSTCo issues.

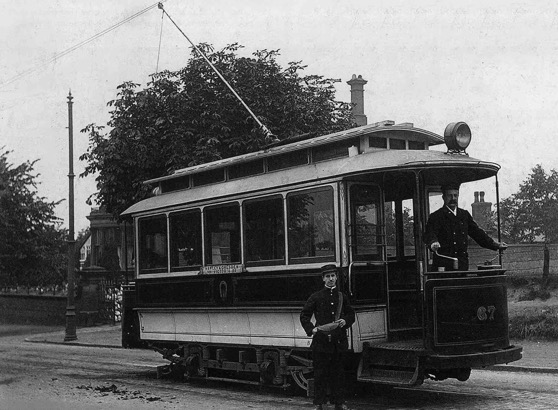

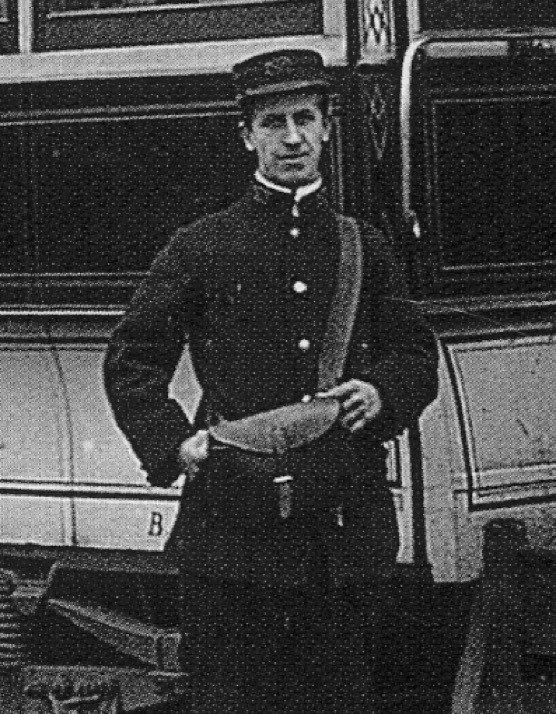

Tramcar No 67 and crew at Longton Park — photo undated, but given the excellent condition of the vehicle, more than likely taken in 1900. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society, with thanks to David Voice.

A blow-up of the above photo showing the conductor. He is wearing a single-breasted jacket with stand-up collars, the right-hand side possibly bearing company or system initials. Once again, the cap badge is not the standard BETCo issue, its form hinting that it may have included a Staffordshire knot.

The crew of bogie tramcar No 76 pose for the cameraman — photo undated, but probably early Edwardian. In contrast to the preceding images, the men here are wearing tunics with breast pockets (with button closures) and epaulettes, along with soft-topped peaked caps.

A blow-up of the above photograph showing the motorman, who is wearing a soft-topped cap, which possibly bears a standard BETCo 'Magnet & Wheel' cap badge (see below).

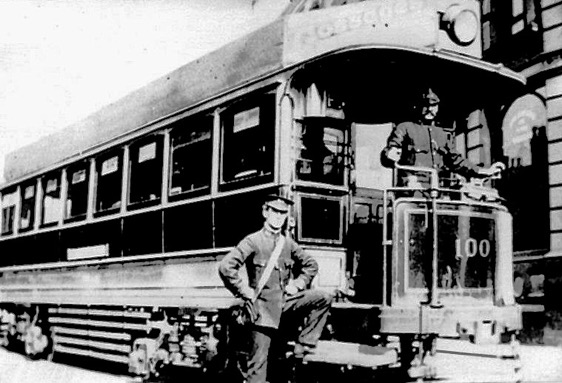

The crew of Tramcar No 100 pose for the camera — photo undated, but possibly mid-to-late Edwardian. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society.

A motorman and three fitters with Tramcar No 84 in the interior of Golden Hill depot — photo undated, but possibly mid-to-late Edwardian. Author's Collection.

An enlargement of the above photo showing the motorman. In contrast to all other BETCo systems (with the exception of those run by the Birmingham and Midland Joint Tramways Committee), his cap does not bear an employee number, but individual metal system initials 'P E T'.

British Electric Traction Company ‘Magnet & Wheel’ cap badges — probably worn from around 1900 onwards — brass. The precise relationship between the two patterns is unclear. Author's Collection.

A very battered Tramcar No 5, festooned with advertisements — photo undated, but almost certainly taken in the mid-to-late 1920s. Although the detail cannot be made out, the caps bear the standard BETCo 'Magnet and Wheel' cap badge, worn above 'P E T' initials. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society.

Tramcar No 80 and crewmen, both in double-breasted greatcoats — photo undated, but probably taken in the 1920s. The conductor is wearing a flat cap rather than the usual peaked cap. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society.

Senior staff

A Potteries Electric Traction Company inspector — photo undated, but probably late Victorian or early Edwardian. The drooping peak cap bears a large, oval, cloth cap badge with the grade in block lettering ('INSPECTOR') and script system initials ('PET'). Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society.

A poor quality photograph of a PETCo inspector, but one which has a particularly interesting back story. The individual depicted is Inspector Ernest E Egerton VC, formally of the Sherwood Forresters. He won his VC in 1917 (when a corporal), but was gassed in 1918, and after the war, could not return to Florence Colliery where he had previously been employed. He eventually found a job with the PETCo as a bus conductor, becoming an inspector in 1928. It is unclear when the photograph was taken, but probably in the late 1920s or early 1930s. In later years, one of the PETCo's successor companies, First Potteries, named a bus after him. Photo and background information courtesy of Levinson Wood.