North Staffordshire Tramways

History

The North Staffordshire Tramways Company Limited was formed on the 4th December 1878 to construct a network of tramway lines in the Potteries. Powers to build and operate the initial tranche of lines were obtained in 1879, the scope of which, in large measure replicated the original vision of the Staffordshire Potteries Street Railway Company Limited; the latter had opened a standard-gauge horse tramway between Burslem and Hanley on the 13th January 1862, but had never managed to extend beyond this.

The NSTCo sought and acquired additional powers to build new lines in 1880, as well as to rebuild the existing SPSRCo line, which it had formally acquired on 17th March that year. Although the NSTCo's powers allowed for the use of mechanical traction, in this case steam, the company initially had to work the SPSRCo line with horses — via a lessee — as it did not yet possess powers to work it with steam traction. The company would have considered horse working to be a temporary expediency pending the rebuilding of this line — to a narrower gauge of 4ft — but in the event it ended up using horse traction elsewhere on the new system, something it had probably not envisaged. The last horse drawn service over the old SPSRCo tracks probably ran on the 28th September 1881, with services over the new 4ft-gauge line that had been laid alongside it commencing the following day.

The first newly built lines to be inspected — in Stoke, Fenton and Longton — were verbally passed for operation on the 22nd April 1881, steam services starting the next day. The line to Longton could, however, only be worked as far as the last passing loop (actually in Fenton), as the company did not have powers to use steam traction beyond Bank House and into Longton proper, due to the narrowness of the roads. Despite this, the lines in Longton had been laid, presumably in the hope of road widening taking place in the not-too-distant future.

The company was also having difficulty with the North Staffordshire Railway Company, which was not being as cooperative as hoped for in rebuilding two canal bridges it owned, effectively stalling construction of the tramway northwards from Stoke to Hanley. The issue was eventually resolved in the tramway company's favour, but only after intervention by the Board of Trade. The company also ran into difficulties constructing all the lines it had powers to build within the timeframe allowed (two years), so it decided to kill two birds with one stone by applying to not only extend the time limit, but also, to use steam on the sections previously denied, primarily those in Longton. Whilst the company got its extension, and approval to use steam, there were two conditions: firstly, that the agreement of the relevant local authority had to be obtained, and secondly, that road widening must take place first. Whilst wholly reasonable on the grounds of safety, the conditions were to prove anything but easy to fulfil, except for Church Street, which Longton Corporation had widened by June 1882, allowing services to be extended to Longton Market Place.

In June 1882, the company was at last able to introduce steam operation between Hanley and Burslem, replacing the horse-drawn services, which seem to have been operated by a Mr Bradford under a lease arrangement (this is not certain). This still left the company working two branches within Stoke (London Road and Glebe Street) by horse traction, though whether this was because they did not possess sufficient engines, or on account of council objections is unclear; it was in fact to be well into 1884 before steam traction was introduced on these lines.

The openings of June 1882 took the NSTCo system to its maximum extent of 6.64 miles, comprising: a main line running southeastwards from Stoke through Fenton to Longton; two branches in Longton, one traversing Stafford Street and Trentham Road to its junction with Rosslyn Road (the Dresden line), and the other travelling down the High Street to its junction with John Street (the Meir line); two branches in Stoke, one southwards down London Road to the West End Hotel and the other northeastwards along Glebe Street to the Copeland Arms; and a line northwards from Stoke from the junction of London Road and Church Street to Hanley, where it turned northwestwards to Burslem, terminating in Newcastle Street at its junction with Blake Street. The tracks beyond Longton Market Place towards Meir and along Stafford Street towards Dresden never saw steam services and were to remain unused for their entire existence; although there is a possibility that they may have been horse worked for a very short period when first opened, this is far from certain.

By late 1882, it was becoming clear that the company had major issues with its tramway engines. The company's engineer had decided, rather unwisely as it turned out, to procure a variety of engines, the majority of them very large and powerful, in order to deal with the stiff gradients on the system. Two Merryweather engines were initially purchased, which proved unequal to the task, quickly being replaced with two larger ones, along with ten very large Manning Wardles, which were more than a match for any incline, even with two trailers in tow. Unfortunately, they were also alarmingly expensive to run (requiring a driver and a stoker, and plenty of fuel), and the sheer weight of the machines was causing significant damage to the track, which turned out not only to be too light for the heavy engines, but for normal ones too. The engineer had also, with the approval of the company, built a huge (and heavy) combined steam engine-cum-passenger car, which turned out to be completely unsuitable, and thus, yet another waste of money. The company had little choice but to replace the entire steam fleet, which it then struggled to sell, even at knock-down prices, despite the fact that most of the engines were barely two years old. On top of this was the not insignificant cost of remediating the track issues, which probably involved complete relaying with heavier rails.

By 1885, however, the company was beginning to see the light at the end of the tunnel, though not without having expended a great deal of money, much to the chagrin of the shareholders. With the new steam fleet performing well and the horse trams finally gone, there remained only the question of the Longton branches. Although the company had had approval to use steam traction (from the Board of Trade) on these sections since 1883, pending road widening of course, it suddenly became lukewarm, attempting to abandon various powers it had acquired for lines which had not been built and which the company no longer wished to build or operate. This move was successfully opposed by various local authorities, including Longton Corporation, so the company simply resorted to abandoning the tracks in Longton without recourse to the BoT, thereby losing its deposit. The tracks in Longton eventually passed into the ownership of the corporation in late 1888/early 1889.

Despite its difficult early years, the NSTCo became a profitable concern, paying very respectable dividends and even building up a reserve fund. In 1895, the company started the process of negotiating with the various councils for their support in converting the system to overhead electric traction and significantly extending it, provided of course that the councils would postpone their right to purchase the tramways (under the various enabling acts). Agreement was eventually reached with them all, including Longton Corporation, which chose to acquire its own tramway powers (obtained in 1896), but then to lease operation to the NSTCo.

Meanwhile, the British Electric Traction Company (BETCo) had appeared on the scene, a company which was embarking on a journey that would see it become a major player in the tramway world. It began by purchasing horse and steam-operated tramways across the British Isles with the intention of converting them to electric traction, as well as promoting schemes for completely new electric tramways, and was destined to own, part-own or lease almost 50 tramway concerns across the British Isles. After a degree of sparring, with the NSTCo no doubt aiming to get the best price possible, agreement was reached and the BETCo, which took a controlling interest in the NSTCo in 1897; the BETCo also reached agreement with Longton Corporation the same year, and in the October, obtained its own powers, including approval to take over those of the NSTCo.

The NSTCo commenced conversion to overhead electric traction in 1897, but before the opening, it was formally taken over — on the 26th January 1899 — by a new BETCo subsidiary, the Potteries Electric Traction Company Limited. The PETCo had been expressly formed to manage the BETCo's interests in the area, and though the NSTCo was effectively now its subsidiary, a rather strange state of affairs existed whereby the NSTCo continued as the owning company (of the tramway), whilst the PETCo operated the system. This complex relationship was only resolved in March 1932 with the liquidation of the NSTCo, almost four years after the closure of the electric tramway.

The first electric services commencing on the 15th May 1899, with the last steam services running in late June 1899; all these services were operated by the NSTCo. The PETCo formally took over operation of the system on the 21st November 1899.

Uniforms

Although the North Staffordshire Tramways Company operated horse tram services itself for around three years, photographs of these services — or the staff working them — appear not to have survived; however, in view of the NSTCo's policy opposite its steam-tramway staff, it seems highly likely that horse tram staff simply wore informal attire.

Fortunately, a small number of good quality photographs have survived of the steam era, which lasted some 18 years almost to the day (1881 to 1899). Steam tram drivers wore typical railway footplate-like attire, namely: cotton trousers and jackets (light in colour), along with soft-topped caps, as well as bowler hats. No badges or insignia were worn. A single photo taken between 1882 and 1884 does, however, show a driver wearing a prominent oval cap badge, possibly cloth and affixed to what appears to be an elasticated hat band, presumably so that it could be simply and easily attached to whatever headgear was worn. Later photographs show a variety of headgear (bowler hats and flat caps), though the oval cap badge is conspicuous by its absence, suggesting that they were only worn for a short period.

The NSTCo also made significant use of stokers due to the size of some of the engines; these men wore the same overall style of cotton workwear as the drivers.

Conductors wore smart but informal attire: jackets, trousers, shirts and ties, along with the fashionable headgear of the day, namely the bowler hat, though towards the end of the system's life, the flat cap was much in evidence. Although none of the available photographs show conductors wearing the cap badge seen in the 1882-1884 photo below, a shot taken in 1899, which includes four conductors, appears to show all of them with an oval badge, very similar in size to the cap badge, but in each case attached to their money satchels.

Fortunately, several photographs have survived which show inspectors. The earliest, taken in 1881, includes four inspectors: they are wearing double-breasted jackets with four pairs of plain buttons and lapels, along with drooping-peak caps topped with a pom pom; the caps bear an oval badge, which was probably of embroidered cloth given that it was non-reflective. A photo taken a couple of years afterwards (1882-1884), shows an individual wearing a smart, mid-length tailored coat, trousers, polished shoes, and a shirt and tie. He is wearing a bowler hat with the same oval badge as the driver (in the same shot), like-wise on some sort of hat band. Whilst he could be an inspector, given the absence of a uniform, he is more likely to be another senior grade such as depot manager. Another photo, taken right at the death of the steam tramway in mid-1899 shows an inspector wearing typical turn-of-the-century 'inspector' garb, namely: a single-breasted jacket with hidden buttons (or more likely a hook and eye affair) and stand-up collars; the jacket was edged in a finer material than the main body, and the collars bore the grade — 'Inspector' — in embroidered script lettering. Headgear still took the form of a drooping-peak cap topped by a pom pom; it bore a large oval cloth cap badge which probably, though not certainly, bore the grade and the system initials. It is possible, however, that this individual was employed by the NSTCo's sister company, the Potteries Electric Traction Company.

Further reading

For a detailed history of the system, see: 'Tramways in the Potteries and North Staffordshire, Part 1' by Harry Dibdin, in the Tramway Review, No 26 (p34-63); Light Railway Transport League (1959). For a history of this and the subsequent electric system, see: 'The Tramways of the Potteries' by David Voice; Adam Gordon Publishing (2018).

Images

Steam tram drivers and conductors

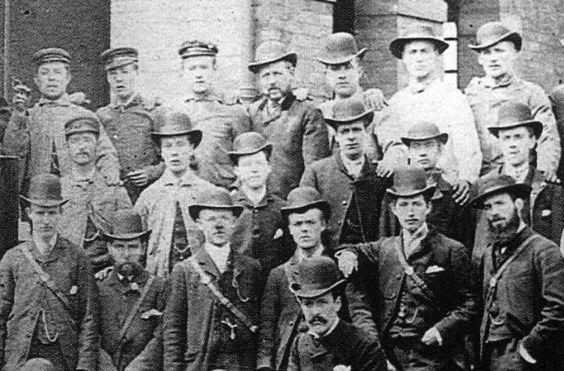

An evocative photo of NSTCo tramway staff taken in 1881, along with one of the early Manning Wardle locomotives delivered in 1881. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society, with thanks to David Voice.

An enlargement of the above photograph showing some of the conductors (at the front) and drivers (at the back). The former are wearing smart but informal attire, whilst the latter are wearing typical footplate attire with either soft-topped caps or bowler hats.

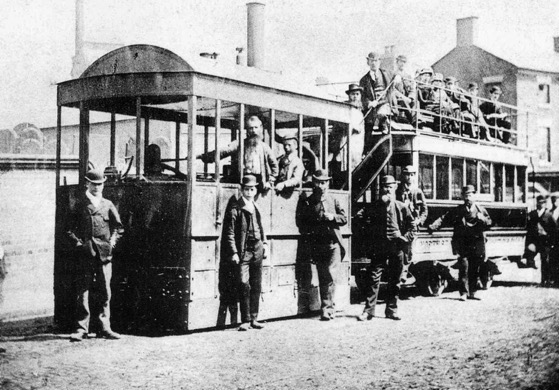

Another early photo, this time depicting one of the two troublesome Merryweather engines, which arrived in 1881, but were gone by 1883/4. None of those depicted are wearing a uniform or a cap badge. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society, with thanks to David Voice.

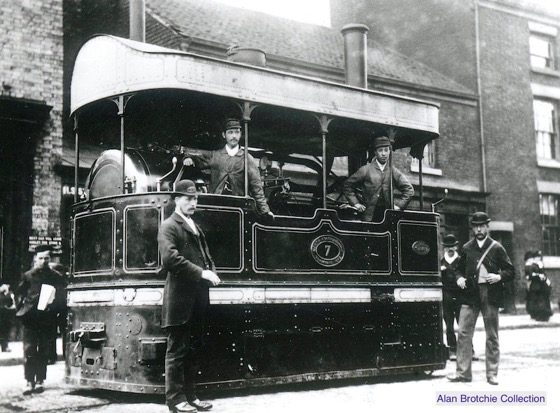

An excellent study of Steam Tram Number 7 (a Manning Wardle product delivered on the 14th April 1882) — photo undated, but as this heavy engine and its sisters only lasted about two years, definitely taken some time between 1882 and 1884.

An enlargement of the above photograph showing the driver, who is believed to be Mr John Lodge; he is wearing typical railway-footplate attire (cotton jacket and trousers) along with a soft-topped cap to which a badge (with hat band) has been affixed. This appears to have three letters at the top, which could well be 'N S T', though this is mere speculation.

Another blow-up of the above photo, this time showing the stoker, the requirement for which made these engines particularly expensive to run compared to others. He is wearing very similar apparel to his driver, though without the cap badge.

Yet a further blow-up of the above photo, this time showing the conductor. Although smart, he is clearly not wearing a uniform, nor does he appear to be wearing a cap badge/licence.

Another relatively early shot, this time of the crew of Steam Tram No 10 (a Beyer Peacock product, and the second engine to hold that fleet number following the demise of the Manning Wardles) outside Bowstead Street depot in Stoke — photo undated, but judging by the excellent condition of the engine, probably taken not that long after delivery (2nd July 1884).

An enlargement of the above photograph showing the tram engine crew — stoker and driver — the former in cloth cap and the latter in bowler and seemingly pristine cotton overalls. Neither man is wearing the cap badge seen in the 1882-1884 photo.

Another blow-up of the above photo, this time showing the conductor. He is wearing a thick coat similar to a modern-day donkey jacket and a bowler hat; once again, there is no sign of the cap badge seen in the earlier photo.

An unidentified Wilkinson Steam Tram in City Road, Stoke-on-Trent — photo undated, but very probably taken in the mid-to-late 1890s judging by the flat caps and the dilapidated state of the engine. The youthful conductor (left) is in informal attire. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society, with thanks to David Voice

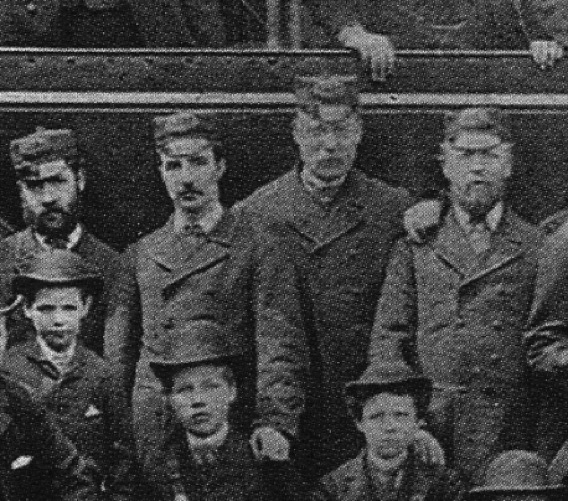

A very late photograph showing an array of staff (fitters, drivers, stokers, conductors and an inspector) in Hanley Park during the reconstruction of Stoke depot (for electrification) — probably taken in early summer 1899.

An enlargement of the above photograph showing two of the conductors, one in a bowler and one in a flat cap, and with what appear to be the badges attached to their money satchels. In fact, closer examination of the photo reveals that all the conductors depicted (four in all) have these badges affixed to their satchels.

Senior staff

An enlargement of the 1881 staff photograph above showing four individuals who are, in all probability, inspectors. They are all wearing double-breasted jackets with lapels, seemingly without insignia of any kind, along with drooping-peak caps bearing an oval badge, topped by a pom pom.

Another blow-up of the 1882-84 photograph above, this time showing an individual who is probably another senior grade such as a depot manager. He clearly has a cap badge similar to that worn by the driver in the same shot, as well as the inspectors in the earlier shot, fixed to his bowler hat by means of a hat band, though he is clearly not wearing a uniform.

An enlargement of the 1899 steam-era photo above showing an assembly of North Staffordshire Tramways steam staff, along with an inspector. Whilst the latter may be an employee of the NSTCo, it seems probable that he was an employee of the NSTCo's sister company, the Potteries Electric Traction Company, which by this time was operating the new electric services. He is wearing typical 'inspector' garb, with a drooping-peak cap topped by a pom pom; his cap clearly bears a large oval cap badge.