Birmingham and Midland Tramways

(including the Birmingham and Midland Tramways Joint Committee)

History

Birmingham Midland Tramways Limited was formed on the 22nd November 1883 to take over and operate a network of 3ft 6ins-gauge steam tramways that were to be constructed by the Birmingham and Western Districts Tramway Company. The latter, which was registered on the 21st December 1882, held powers — under the Birmingham and Western District Tramways Acts of 1881 and 1882 — to construct circa 35 miles of tramway in Birmingham and the towns to its north and west, including the city itself, Balsall Heath, Dudley, Edgbaston, Handsworth, Kings Heath, Kings Norton, Moseley, Oldbury, Rowley Regis, Smethwick, Tipton, and West Bromwich.

Although the B&WDTCo pressed ahead with construction in late 1883, the B&MTL soon found itself struggling to raise the large amount of capital that would be needed to purchase the entire network once completed. A compromise deal was therefore struck with the Birmingham Central Tramways Company and Birmingham Corporation, the former agreeing to take over the lines in Balsall Heath, Kings Heath, Kings Norton and Moseley, and the latter agreeing to construct all the lines within Birmingham, and to then lease their operation to the BCTCo and the B&WDTCo. This left the B&WDTCo to build the remaining lines it held powers for (all outside Birmingham), and to reach a new agreement with the B&MTL (signed on the 12th May 1885) to purchase those lines, and to take over its lease of the corporation-built lines between Summer Row and the city boundary with Smethwick at the junction of Cape Hill and Grove Lane.

The first B&MTL services —between Summer Row (Lionel Street) and Cape Hill — commenced on the 6th July 1885, with the rest of the system following in August 1885. Apart from minor loops and connecting lines, this took the B&MTL steam network to its final size of circa 10.74 miles, circa 2.0 miles of which was leased from Birmingham Corporation. From a stub in Lionel St, Birmingham, the main line ran northeastwards through Smethwick, Oldbury, Tividale, and Burnt Tree to Dudley Station (the junction with Tipton Road). Two branch lines were also operated, between West Bromwich and the main line, one along Bromford Lane to Oldbury, and the other along Spon Lane to West Smethwick. The B&MTL met the tracks of the South Staffordshire Tramways Company at Burnt Tree, and those of the Dudley and Stourbridge Steam Tramways Company at Dudley Station, the B&MTL and the SSTCo having running powers through to Dudley Market Place.

Services were initially operated by 12 Kitson-built steam tram engines, these numbers soon being expanded to 24, though probably not enough to run an adequate service. The company does not appear to have been well managed, with many complaints about the unreliability of the timetable and its sparseness. The financial performance was less than impressive, the company having to issue £10,000 of preference shares in 1887 to pay off the B&WDTCo, though take up was so poor that the latter ended up having to convert some of the money it was owed to a loan.

The poor performance continued through to 1893, the preference shareholders usually getting their full 5% dividend, the ordinary shareholders sometimes 2%, but more often than not, no dividend at all. Services along the two West Bromwich branches appear to have been abandoned in late 1892, presumably because they were loss making, though a service of sorts was eventually reinstated early the following year. This did not last long, as the company duly purchased two horse trams, placing them in operation on the 20th May 1893, but with the services themselves being operated by a contractor, Mr B Crowther.

Things finally began to look up in July 1893 with the appointment of a new manager, the services being overhauled and greatly improved. From here on in the B&MTL appears to have been very well run, passenger numbers rising to circa 9 million, and the ordinary shareholders often receiving a 5% dividend. Moreover, the company undertook extensive track repair and renewal, as well as heavy overhauls of its steam tram fleet.

By 1899, however, it was abundantly clear that the future of the tramway network in the Black Country lay in its conversion to electric traction, and that this would be driven by the British Electric Traction Company. The BETCo had ambitious and well-advanced plans for a large 3ft 6ins-gauge electric tramway system centred on the Black Country and Birmingham, and had by this time already acquired control of several other tramways in the area. On the 29th November 1899, the B&MTL accepted an offer (per share) from the BETCo, which by January 1900, the majority of shareholders had accepted. Around the same time, the BETCo also bought out the B&WDTCo, which held a lease for a tramway line in Birmingham along Heath Street, which had been built, but never operated.

The BETCo now began the long process of negotiating with each and every authority, through whose territory the tramway ran. With the exception of Birmingham Corporation, which owned the tracks within the city, each of the remaining authorities had the right to buy the tramway within their municipal boundary — under the Tramways Act of 1870 — usually after 21 years had elapsed from the passing of the relevant enabling act; although the dates differed slightly, the main one fell on the 11th August 1902. Given the financial outlay involved in converting the steam tramway to electric operation, it was therefore essential that the BETCo reach agreement with each of these authorities, either for them to defer their right to buy, or to purchase the tramways, then lease their operation to the company.

In the event, some authorities chose to purchase the tracks then lease operation to the B&MTL (the Corporations of Dudley and West Bromwich, and Smethwick Urban District Council), whereas others agreed to defer their right to purchase (the Urban District Councils of Oldbury, Rowley Regis, and Tipton). Having secured these agreements, the company obtained powers to electrify the lines, as well as to build a number of extensions; these were granted on the 8th August 1902 under the Birmingham and Midland Tramways Act. Although Birmingham Corporation agreed to electrification of the section of the tramway within the city, the company lease remained at the original expiry date of the 30th June 1906.

The first sections of overhead electric tramway to open were on the Spon Lane and Bromford Lane routes, but only those that lay within the West Bromwich municipal boundary. Therefore, as the tracks between these newly converted sections and the main B&MTL depot (in Smethwick) had yet to be converted, electric operation, which began on the 3rd November 1903, was temporarily handed over to the B&MTL's sister company, the South Staffordshire Tramways (Lessee) Company, which could access the newly converted lines from its main line through West Bromwich. Following the completion of the Spon Lane and Bromford Lane lines, the SST(L)Co took over operation of both (on the 9th March 1904), the B&MTL finally taking over some time during October/November 1904, possibly when the main line between Birmingham (Lionel Street) and Dudley opened, on the 24th November 1904. A new line to Bearwood (from Cape Hill, Smethwick) was opened at the same time as the main line, the branch along Heath Street (leased from Birmingham Corporation) following on the 31st December 1904, and an extension of it (to Soho Station) on the 24th May 1905.

The last horse tram service, operated by Mr Crowther, is believed to have run on the 3rd November 1903, and the last scheduled steam service on the 23rd November 1904.

Although another leased B&MTL line — from Old Hill (near Cradley Heath) to Blackheath — had been opened on the 19th November 1904, it was physically unconnected to the B&MTL network. Although the B&MTL continued to hold the lease (from Rowley Regis Urban District Council), the line was always worked by the B&MTL's sister company, the Dudley, Stourbridge and District Electric Traction Company.

On the 4th December 1903, it was agreed that all the BETCo's Black Country and Birmingham-area tramway interests would be merged into Birmingham & Midland Tramways Limited. From the 1st July 1904, all these systems (operated by Birmingham and Midland Tramways Limited; the City of Birmingham Tramways Company; the Dudley, Stourbridge and District Electric Traction Company; the South Staffordshire Tramways [Lessee] Company; and Wolverhampton District Electric Tramways Limited) were managed as a single entity by the Birmingham and Midland Tramways Joint Committee (B&MTJC). The merger resulted in economies of scale across the enterprise, perhaps most notably in the introduction of a very successful Tramways Parcels Express Service (begun in 1905), and the setting up of a major tramcar building and maintenance facility at Tividale, between Dudley and Oldbury.

With the opening of the extension to Soho, the B&MTL network reached its maximum of size of 12.87 miles, of which 8.1 miles were owned by the company. As in steam days, the main line ran westwards from Summer Row, along Summer Hill to its junction with Heath Street, a branch running northwestwards along the latter to Soho Station. The main line continued westwards to Cape Hill (in Smethwick), where another line branched off southwards along Waterloo Road to Bearwood. The main line continued northwestwards through West Smethwick, along High Street and Oldbury Road to Oldbury, then along Dudley Road, through Tividale and Burnt Tree, to Dudley Station. The tracks met those of sister companies, the SST(L)Co and the DS&DETCo, at Burnt Tree and Dudley Station, respectively.

Although the company's Birmingham leases expired on the 30th June 1906, agreement was reached with the corporation, such that services continued to run through into central Birmingham, these being interspersed with those of the corporation.

The B&MTL was also heavily involved in electricity generation, as well as motorbus operation, the company having set up a new enterprise — Birmingham and Midland Motor Omnibus Company Limited, which became known as 'Midland Red' — to manage all the constituent companies' motorbus interests on the 1st July 1905. On the 13th August 1912, B&MTL changed its name to Birmingham District Power and Traction Company Limited, presumably to better reflect its interests, particularly its expansion into electricity generation and supply. The management committee (the B&MTJC) was restructured in August 1915, when it expanded to include additional BETCo interests (not owned by the BDP&TCo), amongst them the Kidderminster and District Electric Light and Traction Company, owners of Kidderminster and Stourport Electric Tramways. As a result, the name of the committee was changed to the Birmingham and Midland Joint Committee of Electricity, Tramways and Motor Omnibus Undertakings, though the less unwieldy original name (B&MTJC) continued in general use.

The B&MT was in fairly good shape prior to the Great War, the track having been well maintained, and much work done to upgrade the trams themselves, new tramcars as well as major rebuilding having been undertaken. Nevertheless, the Great War still brought much disruption to the tramway, including heavy loadings and greatly reduced maintenance, particularly to the track, the latter due to loss of skilled workers (to the armed forces) coupled with severe restrictions on the availability of new materials.

In 1921, the BDP&TCo attempted to address the looming threat of lease expirations across its tramway network. Although it submitted a parliamentary bill, and entered into lengthy dialogue with the local authorities in an attempt to push the various expirations out to a single date of the 31st December 1938 (in return for significant investment), several of the larger authorities, particularly West Bromwich and Wolverhampton, which were committed to expansion of municipal operation, would not agree to any extension of the company's leases. As a consequence, the resulting bill — the Black Country Tramways and Light Railways Act, 1922 — was almost worthless as far as the company was concerned. The West Bromwich Corporation leases duly expired on the 30th March 1924, and though this spelled the end of tramway operation by the SST(L)Co, a major part of whose services terminated or passed through that municipality, it did not immediately impact the B&MT's Spon Lane and Bromford Lane tramway routes, which the BDP&TCo continued to operate.

Despite bus competition, and the loss of mileage due to the West Bromwich lease expiration, the BDP&TCo continued to turn a healthy profit, though this was largely down to the B&MMOCo's expansion, the latter often deploying its buses to combat the independent motorbus competition. By mid-1924, with the SST(L)Co no longer operating trams, and its two sister companies, the WDETL and DS&DETCo also struggling, the former with impending lease expirations, it was fairly clear to the BDP&TCo that the future of transport provision in the Black Country lay with modes of transport other than the tram. However, this thinking did not necessarily apply to the B&MT, which was not only profitable, but was not in imminent danger of having its tracks municipalised, most of its leases/agreements running through to 1938.

West Bromwich Corporation was anxious to see the back of the Spon Lane and Bromford Lane tramway routes, both being in poor condition, and in 1927, it obtained powers to acquire the portion of both that it did not already own, and to substitute the traction it saw fit. Around this time, the BDP&TCo seems to have rethought the future of the B&MT, reaching agreement to lease operation of the main line between the Birmingham city boundary and Dudley to Birmingham Corporation, as well as the sections of track it owned in Smethwick (Soho) and Bearwood, which the corporation had effectively been operating for many years (as part of the original through-running agreement). Birmingham Corporation duly took over operation of these routes on the 1st April 1928, the Spon Lane and Bromford Lane routes being operated by the DS&DETCo until their closure on the 7th November 1929.

The BDP&TCo, by now only a tramway operator by virtue of its subsidiary, the DS&DETCo, changed its name to the Birmingham and District Investment Trust Limited on the 18th December 1929.

Following the closure of the DS&DETCo's own system on the 1st March 1930, it probably handed over operation of tramway services in Darlaston, which it had been operating on behalf of the SST(L)Co since 1928, back to that company. The last tram service of all on the once large B&MTJC network was withdrawn on the 30th September 1930.

Although now no longer a tramway operator, the B&DIT continued to own various stretches of track until the 31st December 1938, when these were compulsorily purchased by the various local authorities. The last tram service over former B&MTL metals ran on the 30th September 1939, when Birmingham Corporation withdrew services on the Birmingham to Dudley line.

Uniforms

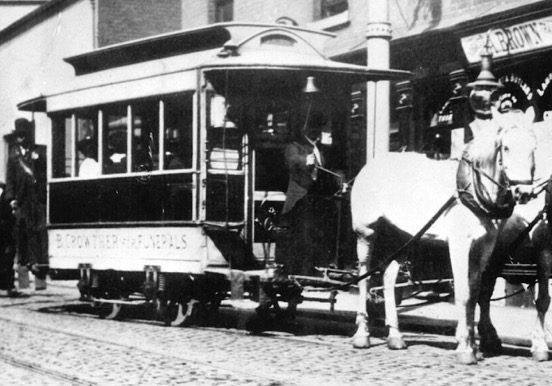

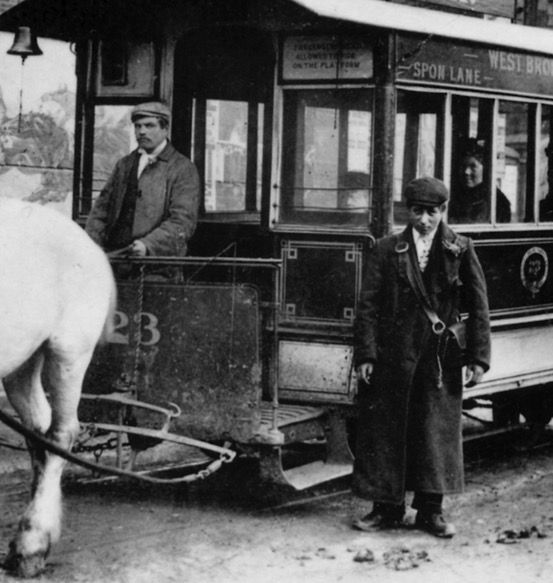

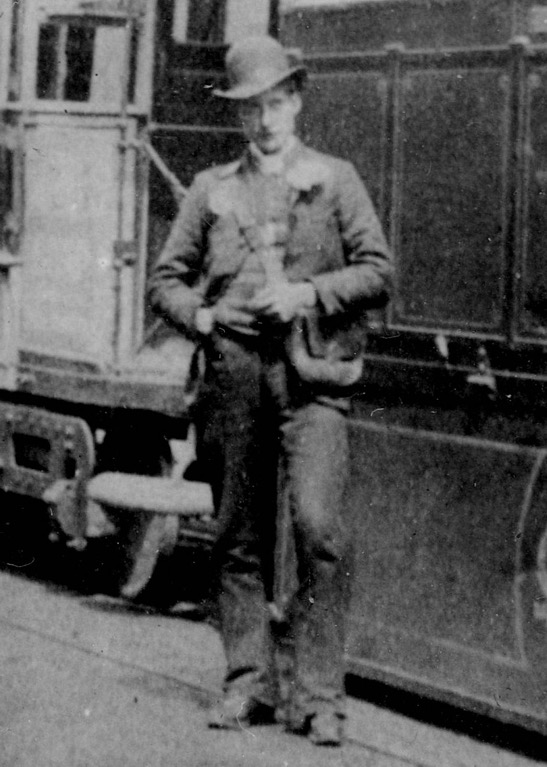

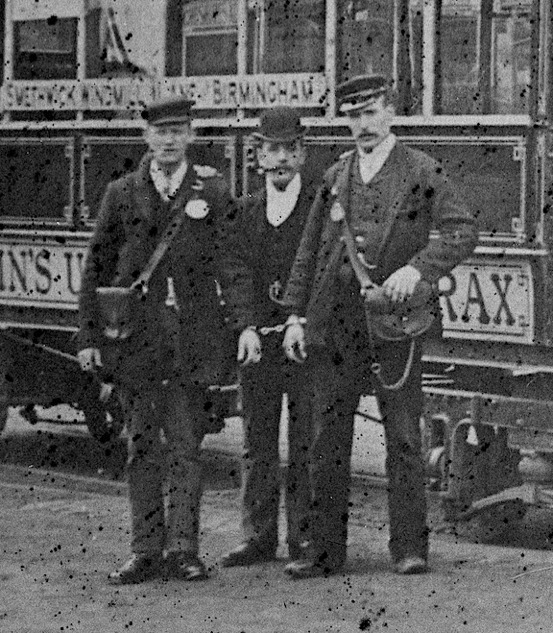

The B&MTL did not operate horse trams itself, instead leasing the services to a Mr B Crowther, who worked them for around ten years, up to their electrification in 1903. Tramcar crews working the horsecar services wore informal but smart attire, comprising trousers, jackets and waistcoats, along with white shirts, ties, and bowler hats, though in later years flat caps seem to have been more the vogue. Staff also wore long, heavy greatcoats, which along with the rest of their work clothing, were presumably purchased by the individuals themselves.

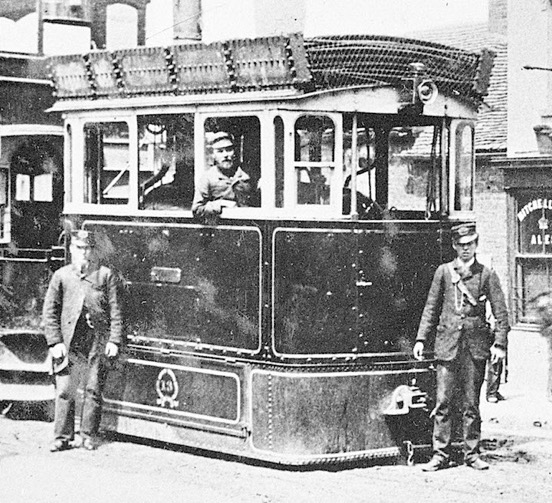

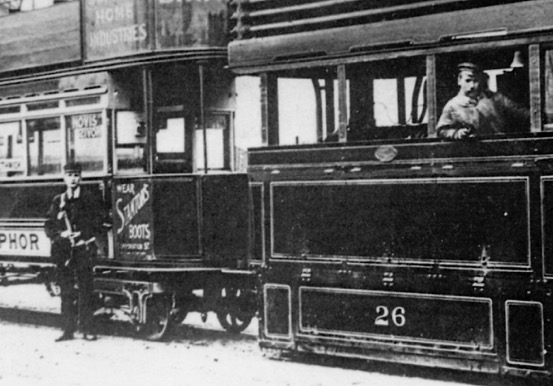

Photographs of the steam-hauled services are relatively common, and a fair few have survived that show tramcar crews in reasonable close-up. In common with the majority of UK steam-operated tramways, drivers wore very similar attire to their railway counterparts, namely, heavy cotton trousers and jackets, often light in colour, along with cotton or soft-topped caps. No badges or insignia appear to have been worn on either the jackets or the caps. In the early years, conductors were provided with single-breasted jackets with five metal buttons (presumably bearing the full company title — see link) and lapels; it is unclear if the latter bore any insignia. Caps were in a drooping-peak style and bore a large and distinctively shaped cap badge. For some reason now unknown, it would appear that the company ceased to issue uniforms, possibly from as early as 1886/7. Although photographs taken after the 1880s clearly show staff wearing single-breasted jackets with lapels, and soft-topped caps, the jackets did not bear reflective buttons (suggesting that they were not metal, and therefore not uniforms per se), nor did the caps carry a cap badge.

Conductors working within the confines of Birmingham during the steam era were required to wear a round licence badge that bore the arms of Birmingham, a number and the grade ('CONDUCTOR'); for some reason, this requirement seems not to have been applied to steam engine drivers, though they may have had them but simply didn't bother to wear them. There are two types of licence badges, which almost certainly reflect the situation prior to, and after, the full grant of arms to the city in April 1889 (see below).

Although the B&MTL was taken over by the British Electric Traction Company in 1900, the latter appears to have been content to continue the policy of its predecessor, only issuing new uniforms following electrification in late 1904. Over the course of its history, the BETCo either owned, part-owned or leased almost 50 tramway concerns in the British Isles, across which it largely imposed a standard uniform policy. Although jackets appeared to vary somewhat between BETCo systems, as well as across the decades, the cap badges, collar designations and buttons invariably followed a standard pattern. However, in the case of the BETCo's Black Country and Birmingham systems, the parent company appears to have initially allowed each of its operating companies a degree of autonomy, and this was certainly reflected in the uniforms worn. Initial issues to B&MTL electric-car staff were single-breasted with five buttons (of the standard BETCo 'Magnet and Wheel' pattern — see link), with a single pocket on the left breast (with button closure and pleat) and stand-up collars; the latter probably carried system initials on the bearer's right-hand side and an employee number on the left, though these cannot be made out with certainty on surviving photographs. The tensioned-crown peaked caps bore off-the-shelf, script-lettering grade badges — either 'Conductor' or 'Driver' — rather than the standard BETCo 'Magnet & Wheel' cap badge, which was used by all other BETCo electric tramways outside of Birmingham. The jacket and cap badges were almost certainly brass.

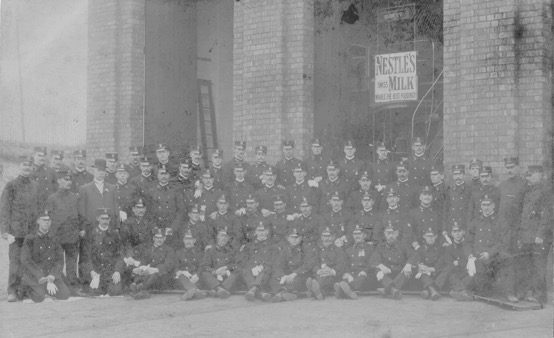

Following the creation of the B&MTJC on the 1st July 1904, a standard uniform policy was eventually imposed across all the constituent companies, including the B&MTL. Motormen and conductors were issued with double-breasted jackets with four pairs of buttons and high, fold-over collars; the latter carried individual metal initials — either 'B M T' or 'B & M T' — on the right-hand side and an employee number on the left-hand side, almost certainly in brass. Surviving examples suggest that the first collar badges may have had diagonal striations giving a rope-like effect (see below). At some point, the employee number was dispensed with, leaving the left-hand collar badgeless. Caps were of the drooping-peak type, and carried a prominent oval brass cap badge comprising intertwined 'BMT' initials beneath the 'Magnet and Wheel' device, all within a wreath (see below).

Staff working the new electric services probably wore a new, smaller design of municipal licence badge, possibly introduced at the same time as these services, i.e., in late 1904.

At some point prior to the Great War, the caps were changed to a tensioned-crown peaked type, though they continued to carry the same cap badge. Jackets varied subtly in style across the decades, always double-breasted, but sometimes with four pairs of buttons and sometimes five, and with three waist-level pockets. The jackets could be worn buttoned up to the neck or open, the latter giving the impression of a lapel jacket; the collar insignia remained unchanged throughout the life of the tramway. Double-breasted greatcoats were also provided; these had high, fold-over collars that carried the same badges as the jackets worn underneath.

Photographs of inspectors indicate that they wore single-breasted jackets with hidden buttons (or more likely hook and eye fasteners) and stand-up collars; the latter bore 'Inspector' in embroidered script lettering. Caps were initially of the drooping-peak type, though these were later superseded by tensioned-crown peaked caps. During B&MTJC days (i.e., 1904 onwards) the caps carried the grade — 'Inspector' — in embroidered script lettering, as well as the standard B&MTJC cap badge (worn above the grade badge).

Female staff were employed during the Great War to replace men lost to the armed services; they were definitely employed as conductresses, though whether they were also employed as motorwomen remains unclear. These ladies were issued with tailored, single-breasted jackets with five buttons, lapels, and a belt with button fastening; it is currently unclear what insignia was worn on the lapels, though they may simply have been left plain. Headgear took the form of a dark-coloured straw bonnet or a baggy motor cap (probably for summer and winter wear, respectively); these bore the standard B&MTJC cap badge, attached to a ribbon in the case of the bonnet. Double-breasted, lancer-style greatcoats were also provided; these had five buttons, epaulettes and high, fold-over collars; the latter usually bore system initials on the right-hand collar only, but were also frequently left plain.

Further reading

For a general history of the B&MTL (and B&MJTC), see: 'Black Country Tramways Volumes 1 and 2', by J S Webb; self-published (1974 and 1976).

Images

Horse tram drivers and conductors

A horsecar operated by Mr B Crowther (who may be one of those depicted) at the West Bromwich terminus of the Spon Lane route, which he worked on behalf of Birmingham and Midland Tramways Limited — photo undated, but probably taken in the mid-1890s. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society, with thanks to David Voice.

B&MTL-owned Horsecar No 23 at West Bromwich — photo believed to have been taken in 1900. Both men would have been employees of Mr B Crowther, to whom the Spon Lane services, and two B&MTL horsecars, including this one, were leased. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society, with thanks to David Voice.

Steam tram drivers and conductors

A driver, a conductor (right) and possibly an inspector (left?) with Thomas Green-built Steam Tram No 13 outside the Cape of Good Hope Inn in Smethwick in 1885, the year the engine was built. The conductor and inspector are clearly wearing uniforms and drooping-peak caps, the latter bearing prominent cap badges. With thanks to the National Tramway Museum.

B&MTL Kitson-built No 7 (delivered in 1885) along with an unidentified trailer. Judging by the style of the conductor's bowler hat, with its upturned brim, and the good condition of the engine, the photo was probably taken around 1886/7.

An enlargement of the above photograph showing the conductor. He is not wearing a uniform, but does have the usual licence badge attached to his cash-bag strap.

Two conductors pose in front of Steam Trailer No 17 at West Smethwick depot — photo undated, but probably taken in the late 1880s or early 1890s. By this time, the company had clearly stopped issuing uniforms and cap badges. Both men are wearing municipal licence badges, probably of the pattern shown below. With thanks to the National Tramway Museum.

Birmingham municipal licence badge — brass — of the type that was probably issued to B&MTL conductors prior to 1889. In April 1889. a full grant of arms was made to the city, including supporters and crest, after which the licence badges were presumably updated. Author's Collection.

Birmingham municipal licence badge — brass — of the type that was probably issued to B&MTL steam-tram conductors from 1889 onwards, following the full grant of arms to the new city.

Birmingham municipal licence badges, pre-1889 (top) and 1889 onwards (bottom) — brass. This oval pattern of licence badge may well have been used at some point, though photographic evidence for this is completely lacking. Author's Collection.

Rebuilt B&MTL Kitson Steam Tram No 18 and Steam Trailer No 18 (?) in all likelihood outside Windmill Lane depot — photo undated, but probably taken in the late 1890s. With thanks to the National Tramway Museum.

An enlargement of the above photograph showing the conductor's attire.

An excellent illustration of the filthy nature of the work involved in working steam tram engines, in this case, Kitson-built B&MTL No 11 — given the battered condition of the engine, the photo was probably taken at Windmill Lane depot around the turn of the century. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society, with thanks to David Voice.

An enlargement of the crew photograph above, showing the conductor on the platform of Steam Trailer Car No 17. A round licence badge is clearly dangling from the subject's cash-bag strap. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society, with thanks to David Voice.

A driver and a conductor with B&MTL-assembled Kitson Steam Tram No 26 on a Birmingham-Windmill Lane-Smethwick service — photo undated, but probably taken around the turn of the century given that the trailer was built in 1899. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society, with thanks to David Voice.

Birmingham municipal driver's licence badge (No 122) — brass. This pattern of badge was possibly issued to steam tram drivers working services within Birmingham, though there is currently no photographic evidence that would either support or refute this. Author's Collection.

Motormen and conductors

A youthful B&MTL conductor and his motorman with Tramcar No 7 in St Paul's Rd, Smethwick — photo undated, but judging by the relatively good condition of the tram, probably taken in 1904 or 1905 (it was built in 1904). Both men are wearing script-lettering grade cap badges. The standard BETCo 'Magnet & Wheel' cap badge is nowhere to be seen, despite the fact that the tram side panel carries it prominently (not shown). A Photo courtesy of the National Tramway Museum.

General pattern script-lettering brass cap badges — 'Driver' and 'Conductor' — of the type used by the B&MTL. Author's Collection.

Birmingham municipal ‘CONDUCTOR’ licence badge. This is possibly the pattern of licence badge issued to all conductors working electric services within Birmingham — including companies and the corporation — from the early Edwardian era through to the Great War. Author's Collection.

Birmingham municipal ‘DRIVER’ licence badge. This is possibly the pattern of licence badge issued to all motormen working electric services within Birmingham — including companies and the corporation — from the early Edwardian era through to the Great War.. Author's Collection.

An excellent shot of a B&MTJC tramwayman (No 100) — photo undated, but very probably mid-Edwardian. It is unfortunately impossible to know which of the five constituent companies of the B&MTJC he actually worked for. Photo courtesy of the Stephen Howarth Collection.

An enlargement of the above photograph showing details of the collar insignia (individual 'B & M T' initials and employee number, '100') as well as the cap badge, an example of which is depicted below.

Birmingham and Midland Tramways Joint Committee cap badge — brass. This was introduced some time after 1904, when the B&MTJC came into being. Note the use of the parent company's (British Electric Traction Company) 'Magnet and Wheel' symbol.

Probable B&MTJC early 'rope effect' collar initials and collar number; these were eventually superseded by plain brass letters/numbers. Author's Collection.

A badly faded photograph, but one which shows a B&MTJC motorman at the controls of a tramcar, in this case No 22 — photo undated, but probably mid-to-late Edwardian. Author's Collection.

An enlargement of the above photograph showing the motorman. He is wearing a Birmingham licence badge, which together with the destination blind, indicates that he was working for either Birmingham and Midland Tramways or South Staffordshire Tramways.

The staff of an unidentified B&MTJC depot, which is possibly either Dudley or West Smethwick — photo undated, but probably taken around 1905/6. Author's Collection.

Two B&MTJC employees (Numbers 33 and 72) who, judging by their gaiters, are possibly motor omnibus drivers — photo undated, but probably mid Edwardian. Photo courtesy of the Stephen Howarth Collection.

An enlargement of the above photograph showing Employee No 33; his collars bear 'B M T' system initials rather than 'B & M T'.

B&MTJC employee No 327 — photo undated, but probably mid-to-late Edwardian. Rather than a drooping-peak cap, the subject is wearing a more modern tensioned-crown peaked cap. The presence of a licence badge suggests that he worked within the Birmingham municipal boundary, so he would have been employed by either the B&MTL, the CofBTCo (up until 1911) or the SST(L)Co. Author's Collection.

Senior staff

An enlargement of the 1905/6 staff photograph above showing one of the inspectors.

A B&MTJC inspector at a City of Birmingham Tramways Company depot circa 1906/7 — the tram in the background is No 229. Author's Collection.

Female staff

A B&MTJC Great War conductress. She is wearing a lancer-style greatcoat devoid of badges, and a baggy motor cap bearing the standard B&MTJC cap badge. It is unfortunately not possible to say which of the B&MTJC's tramways she worked for, though as she is wearing a Birmingham licence badge, it would have been one of only two B&MTJC tramways who services penetrated the municipal boundary at this time (i.e., the B&MT or South Staffordshire Tramways). Photo courtesy of Dr Paul Collins.